Ninth in series

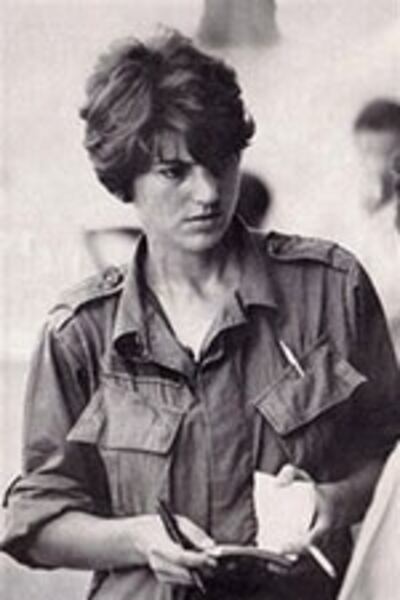

New Zealand-born Kate, who died of cancer on May 13, 2007, made her name as a reporter when she began covering the Vietnam War.

By her own account, Kate reached South Vietnam’s capital with “no job lined up and only an old Remington typewriter, the name of a UPI photographer, and a couple of hundred dollars” in her pocket.

UPI bureau chief Bryce Miller gave her free-lance assignments but no steady job.

“What the hell would I want a girl for?” Miller asked, according to Kate.

Bryce’s attitude was typical of the era, when women war reporters were rare.

In early 1966, about a year before Kate arrived, UPI sent me—like any beginning field reporter based in Saigon—to cover U.S. troops. I worked sometimes out of Da Nang and the Central Highlands, from locations with names like Landing Zone Dog.

Then UPI decided that I should cover the “Vietnamese side of the war,” from politics to refugees and “pacification.” The beat also included whatever I could find out about the Viet Cong and their backers in North Vietnam.

It was a lucky break for me, because it opened up a whole new world of uncovered stories.

For a few months, Kate Webb became my “gofer,” as she described it, on the Vietnamese beat. Together, we formed what Kate called the “political staff.” But that staff was just two of us out of a total of some 10 reporters and four or five photographers. Everyone else was covering the “American war.”

Kate went on to cover the war for six years for UPI, including a stint in Cambodia in 1971 when she was captured by the Viet Cong and held prisoner for 23 days. Kate developed a bad case of malaria before being released.

At one point during her ordeal, Kate was given up for dead. The New York Times published her obituary.

Like many news agency reporters, Kate never promoted herself. She was a good listener, quiet and self-effacing, often speaking in a murmur. But if someone crossed or misled her, she could turn blisteringly direct.

What I remember about Kate was her ability to get to know people wherever she went. As Kate described it in a fine book written by women war reporters, she tended to find her friends among the Vietnamese “from MPs, journalists, priests, and students to soldiers, bar girls, and street kids.”

In that book, titled War Torn, Kate says that in later years when her thoughts returned to Vietnam, it was often to Captain Truong of the South Vietnamese army's 1st Division. The division was often described as the Vietnamese army's best.

The captain’s soldiers were, unlike the American GIs, in for the duration. His company operated at night without helicopter support. The men carried their wounded out on foot.

Kate was there when Captain Truong was wounded. When his number two man was hit, Kate helped to carry him on a stretcher back to headquarters, where his arm was amputated. And she went with the captain’s men on their “pitch-black night patrols with only the tiny phosphorous mark on the pack of the man in front” of her to follow.

As Kate noted, the U.S. newspapers at that stage were “not much interested” in the South Vietnamese army, but Kate was.

So was a reporter named Paul Vogel, who spoke fluent Vietnamese and worked for UPI in the late 1960s up until the fall of Saigon.

When I think of Kate, I also think of Paul because he, too, got to know the Vietnamese.

Paul started as a stringer for UPI and went on to do a remarkable story in 1975 about a flight that left Da Nang for Saigon during the final days of the war overloaded with desperate South Vietnamese soldiers who fought and clawed their way on board in order to flee the relentless advance of North Vietnamese troops. A few of them even stuffed themselves into the wheel wells as the plane took off.

Unfortunately, Paul never got anything like the recognition that Kate received.

Compared with the hundreds of foreign correspondents who focused for the most part on the American forces, the reporters working the Vietnamese side were small in number. And that was the case all the way from the mid-60s into the early 70s.

When I later saw Kate for the first time in decades, back in 2002, she graciously thanked me for helping her out back in 1967.

But If I recall correctly, all I did was introduce Kate to a few Vietnamese contacts. I also gave her a couple of story ideas.

Like any good reporter, Kate took it from there.