In the coming months, Laos’ ruling Communist Party will begin informal discussions about the country’s future leadership, which will be finalized ahead of the National Congress in January 2026. The top three leadership positions are expected to see new faces.

According to sources, Thongloun Sisoulith, who has served as both prime minister and party chief, is likely to step down. His probable successor as party chief is Saysomphone Phomvihane, the current National Assembly chair and scion of the influential Phomvihane family.

Meanwhile, Sommath Pholsena, one of the five deputy chairs of the National Assembly, is expected to succeed Saysomphone in parliament. Sommath, of Chinese descent, is the son of Quinim Pholsena, who served as foreign minister in the 1960s.

Interestingly, Sommath was a childhood friend of Chinese President Xi Jinping, having studied together at Zhongnanhai, the Chinese Communist Party leadership compound in Beijing.

They are thought to still be on good terms. These close ties could prove useful as Vientiane depends on good relations with China.

The political landscape, however, is complex and largely depends on Prime Minister Sonexay Siphandone. A heir of the powerful Siphandone clan, Sonexay is believed by some sources to be maneuvering for either another term as prime minister or a promotion to party chief in 2026.

If successful, it could result in a Siphandone-led premiership and a Phomvihane-led party — a potentially balanced outcome in Laos’ dynastic politics. However, the prevailing belief is that Sonexay is on his way out.

Laos is grappling with severe economic and social crises since 2021. The economy has been decimated, the inflation rate is one of the highest in the world, and the local currency is still in freefall.

Schools lack both teachers and students, and university corridors remain eerily empty. The private sector has been gutted, as many Laotians have emigrated to Thailand for work or abandoned full-time employment to focus on family businesses.

Ministries are so short-staffed that they struggle to perform basic functions. Every month brings uncertainty over whether the government can pay the service costs on its colossal national debt, which now stands at approximately 130% of GDP.

External factors

On the one hand, Sonexay cannot be entirely blamed for these issues. Many of Laos' economic problems stem from external factors, such as interest rate hikes by foreign central banks, or from decisions made by Lao leadership a decade ago.

The decision in the early 2010s to focus on attracting hydropower investments, rather than building robust manufacturing or service sectors, was not Sonexay’s choice.

On the other hand, Sonexay headed the emergency economic task force under his predecessor and, knowing that it can do little to improve things, the communist party has contented itself with finding scapegoats.

The central bank governor was replaced earlier this year, though neither he nor his successor have the power to address Laos' macroeconomic challenges.

An earlier scapegoat was Phankham Viphavanh, who became prime minister in early 2021 at the onset of the crisis but resigned less than two years later — making him Laos' shortest-serving premier.

While Phankham cited health reasons, insiders indicate that party leaders had already decided he should step down due to poor economic management and personal scandals.

Sonexay, seen by many as the rising “princeling” of the party, succeeded Phankham in December 2022. But the move may have come too soon.

The economic crisis was never likely to be short-term and, aged 55 at the time, Sonexay had only completed one full term on the Politburo, ranking ninth when it was formed in 2021.

The original plan had been to allow him another decade to gain more experience, with a possible ascent to prime minister or party chief in the 2030s, when he would be in his 60s — the optimal age for a Laotian leader.

Rival families

Now, however, Sonexay’s political future hangs in the balance. If he fails to retain his position or secure a promotion by 2026, it could signal the end of his career, despite his relative youth.

His family has a vested interest in his success: Sonexay is the eldest son of Khamtai Siphandone, the party chief from 1992 to 2006, and who, now aged 100, remains an influential figure behind the scenes.

I’m told Khamtai is lobbying hard for his son to stay in power, especially given the possibility that Saysomphone Phomvihane — heir to the rival Phomvihane family — may ascend to the role of party chief.

Nevertheless, if Sonexay is removed, the Siphandone family’s influence may remain intact.

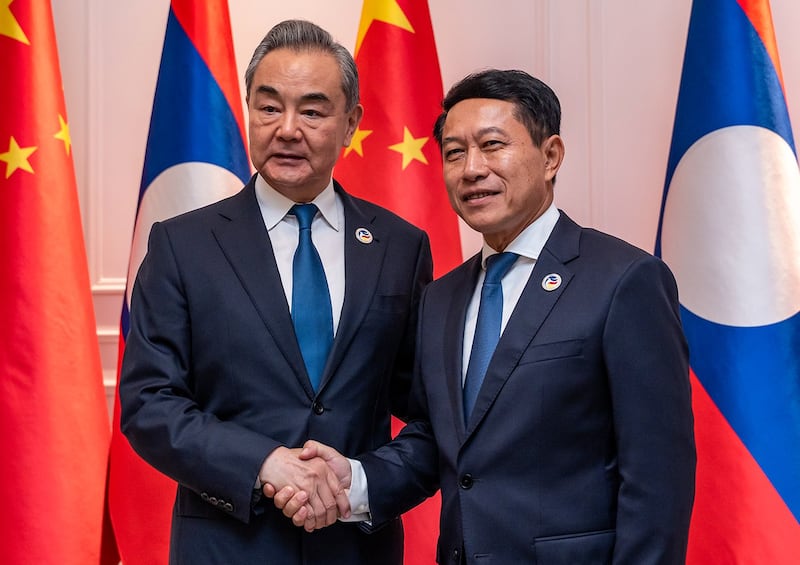

Amid these family rivalries, talk has emerged that Saleumxay Kommasith, the current foreign minister and a deputy prime minister, is poised to become the next prime minister.

Saleumxay hails from Houaphanh province, the revolutionary heartland in northeastern Loas — as does Thongloun — and from a powerful political lineage.

His father, Maj. Gen. Thonglai Kommasith, was a close confidant of former President Choummaly Sayasone. Saleumxay’s younger brother, Malaithong Kommasith, the current commerce minister, is married to one of Khamtai Siphandone’s daughters.

It is said that Saleumxay isn’t universally popular within the communist party. Many consider the 55-year-old to be an upstart who has risen too quickly thanks to patronage and favor.

As well as his familial connections to the Sayasones and Siphandones, he was a protegee of Thongloun, the current party chief, who was foreign minister before becoming prime minister in 2016.

Rising ministry influence

Other ministries are displeased that the foreign ministry has gained so much influence over the past decade; the communist party knows that domestic policy turns on foreign relations.

Even before gaining more institutional influence within the party, the foreign ministry had long enjoyed access to corrupt slush funds that buy loyalty, which is denied to some other ministries, another reason for the jealousy.

Though not universally liked, Saleumxay is widely acknowledged as one of his country’s most competent technocrats.

One of the few senior cadres to be educated in the West, he has a reputation as a skilled diplomat and is regarded as politically neutral — or opportunistic and protean, depending on the perspective.

He is well aware of Laos’ dependency on China and Vietnam but has also sought to improve ties with the West, particularly through securing recent Western financial support for environmental and poverty-reduction initiatives.

RELATED COMMENTARIES

[ COMMENTARY: Laos cannot dam the emigration floodOpens in new window ]

[ COMMENTARY: Laos can feed itself, but its food security is complicatedOpens in new window ]

[ COMMENTARY: Weak governance, poor economy drive the hollowing out of LaosOpens in new window ]

Moreover, his reputation has increased massively this year, with Laos holding the annually-rotating ASEAN chair. Saleumxay has been behind the scenes micromanaging the process, even if Sonexay and Thongloun are front-and-center.

One of my sources put it: Saleumxay is “a safe pair of hands: skilled in diplomacy, very discreet, smooth, urbane, cosmopolitan”. Another remarked that he has “won his spurs” through his work organizing Laos’ chairmanship of the Southeast Asian bloc.

Despite the economic turmoil, Sonexay recently called on “people from all walks of life [to] come together as good hosts” ahead of next month’s ASEAN Summits in Vientiane.

No amount of government propaganda will convince ordinary Laotians that the country is on the right track nor feign interest in foreign dignitaries zipping past in limousines on closed-off streets.

But, behind the scenes, the summits could mark a turning point in Laos’ leadership battleground.

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. He writes the Watching Europe In Southeast Asia newsletter. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.