As the war in Ukraine drags on, with no clear-cut Russian victory in sight, we are seeing important parallels with the conflict in Myanmar, which has fallen from the headlines.

The Russian offensive in Ukraine has faltered, and there has been a heavier reliance on indiscriminate air attacks with non-precision guided munitions and artillery. The Russians don’t have sufficient forces to capture and hold cities, so they surround them and use long-range artillery fire.

They are intentionally targeting civilians, apartment blocks, and hospitals. Like Myanmar's military, Russian forces have laid siege and prevented humanitarian convoys from reaching civilians. There can be no pretense that this is simply collateral damage.

The Tatmadaw, as the Myanmar military is known, has razed villages, burning down at least 6,700 homes, according to the group Data for Myanmar. It's a punitive act because they cannot hold territory. And yet their ruthless "Four Cuts" strategy - employed for decades to deny insurgents support from local people - has not deterred the public from supporting the shadow National Unity Government since last year's coup.

Both Russia and Myanmar rely on poorly trained, conscript militaries, with low morale. As Russian forces have been depleted through deaths, injury or desertion, we are seeing the leadership call up mercenaries from Chechnya, Syria, and their own Wagner Group, a Russian paramilitary organization. In Myanmar, where the Tatmadaw has been slowly hollowed out, there is greater reliance on the pro-junta Pyu Saw Htee militia.

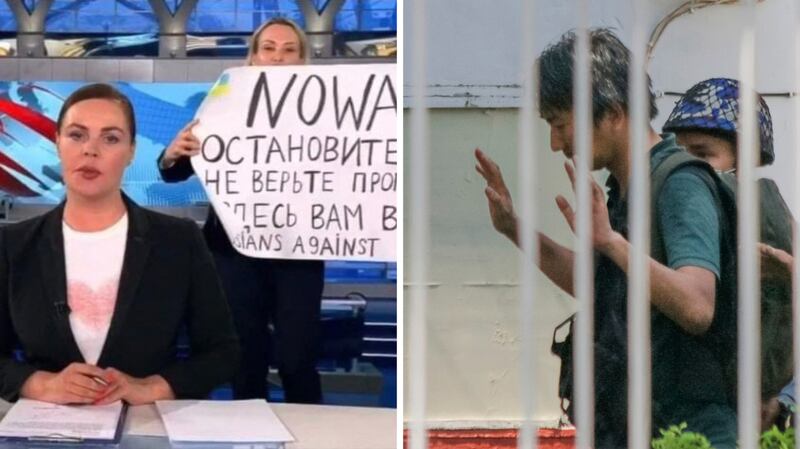

Both regimes have stepped up arrests of dissenters. Russia has imposed almost a total blackout of media not under state control, forcing most foreign reporters from its borders. Russia is transforming its internet into a Chinese-style intranet. In Myanmar, there have been attempts to shut down the internet in the conflict-wracked regions like Sagaing to prevent evidence of government atrocities, while policing social media to target dissent. In both countries, the assaults and arrests of journalists continue apace. As in the towns and cities that the Russians occupy, the Myanmar military has been summarily executing civilians.

The leadership of both countries believe that if they act with enough violence they can submit the civilian population to their will and will be able to evade all accountability. In recent fighting in Myanmar, over five dozen civilians were burnt to death. Neither government tries to hide their war crimes; indeed they want them there for all to see, as a warning of things to come.

There is a shared belief that they can weather international sanctions and both governments are displaying callous disregard for the economic crisis that they are causing their populations. Both have quickly reversed over a decade of economic progress. The junta in Myanmar oversaw an 18 percent contraction of the economy in 2021, and more than half the population now lives in poverty. Both regimes are sanctioned, and have seen much of their trade diminish. Today the citizens of Yangon are experiencing electric shortages and a lack of water.

The wars in both countries have seen incredible courage against all odds. We’ve witnessed valiant fighting by Ukrainians defenders as well as by Myanmar’s People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) and their allied Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs). But they are up against insurmountable odds. Even if the Tatmadaw has a smaller fighting force than is often suggested, it is still larger and better resourced than the PDFs, with the power of conscription.

Like the Russian army, the Tatmadaw is weaker and more poorly armed than budgets would suggest because of endemic corruption. Authoritarianism tends to weaken most institutions including the security services. When PDFs display captured equipment or army prisoners of war, it’s pretty shocking how poorly armed and equipped they are, given the military’s primacy and budget. But clearly much of the military budget goes to prestige items while young conscripts fighting the war remain poorly fed, armed, and equipped.

The PDFs continue to have significant challenges in raising funds and acquiring arms and ammunition. Recently we’ve seen several battles that have left about dozen PDF personnel killed having run out of ammunition. The NUG just announced that their PDFs will have a $30 million budget this year. While that’s significant amount for sub-state militia, it is paltry compared to the resources of the Tatmadaw. Just through their asymmetrical dominance in materiel, the Russian military and the Tatmadaw are able to grind out a long war.

Like the Ukrainian forces, the PDFs and their affiliated EAOs have high morale, relatively good discipline, and a just cause that they are fighting for. They hold themselves to higher standards on the battlefield in terms of trying not to commit war crimes, intentionally target civilians, or looting and pilfering. And unlike the Tatmadaw or the Russians, they enjoy overwhelming popular support.

The one thing that the PDFs and EAOs have not focused on sufficiently is targeting the Tatmadaw’s long and vulnerable supply lines. The Myanmar military has never fought on as many fronts simultaneously and they have never had to fight in the ethnic majority Bamar heartland. The Ukrainians have taken advantage of this vulnerability to a much greater degree. While the NUG may beg for the provision of manpads – portable, surface-to-air missiles - the best way to target the military’s air assets is by targeting the supply of jet fuel.

As much as we can root for the underdogs in Ukraine and Myanmar, neither is likely to win a clear-cut military victory. But they don’t have to. Guerrilla forces simply have to not lose. They have to wear down the occupying force, trap them in a war of attrition that forces them to further alienate the population through barbaric attacks and systematic human rights abuses. And in that regard the PDFs are doing admirably.

In both cases, the way the conflicts likely end is from within. In Russia, the oligarchs may not pose a challenge to President Vladimir Putin simply because they do not control any coercive instruments. The threat Putin faces comes from his own security services, which he appears to be scapegoating for the military’s poor performance.

The real threat to junta leader Min Aung Hlaing and his deputy Soe Win comes from lower-ranking generals and colonels who have not shared in the military regime's spoils. These are the people who have to execute the war and who understand that given the rate of casualties and defections that they do not have the manpower to hold territory. These are the people that know how despised the military is and how little legitimacy its regime has. They are the people who know that the war is unwinnable and have an interest in protecting what's left of the military's political, economic, and institutional interests. They know they can only do that through a negotiated settlement and that is impossible with this senior leadership still in place.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or RFA.