After nearly four decades in office, Hun Sen this week steps down as Cambodia's prime minister. The National Assembly sat for the first time Monday, one day before the new premier is set to be sworn in. On Aug. 22, he will hand power over to his eldest son, Hun Manet, who was just 8 years old when his father took charge of a communist regime embroiled in a civil war and held afloat, barely, by foreign aid.

The 71-year-old strongman prime minister is bequeathing his son a country that has changed considerably over the course of his reign. Cambodia is on track, by World Bank estimates, to reach upper-middle income status by 2030, but inequality is rampant and poverty remains widespread.

The government Hun Manet, 45, inherits is one where it pays to have powerful parents. His incoming defense minister, Tea Seiha, is the son of his father’s long-serving defense minister, Tea Banh, who was appointed in 1989. His new interior minister, Sar Sokha, too, is taking over from his own father, Sar Kheng, who has held the top security position for 31 years.

It’s a generational change of government taken to its most literal extreme. The new minister of commerce, Cham Nimol, is the daughter of Cham Prasidh, who ran the ministry from 1994 to 2013. The minister in charge of the civil service, meanwhile, is Hun Manet’s younger brother, Hun Many. Control of Cambodia’s central bank is passing from Chea Chanto, in charge since 1998, to his daughter, Chea Serey.

In fact, almost a quarter of the 125 ruling party candidates who ran in the July 2023 national election are related, according to a recent analysis by the Cambodian Journalists Alliance Association.

The newest government reflects the Cambodia that Hun Sen has built through decades of political violence and institutional control. It is one where absolute poverty has fallen, but where an idealistic system of electoral government created by the United Nations in the 1990s has been transformed into a constellation of family fiefdoms, glued together only by a knack for corruption.

“It is a ‘clanic’ succession; it is a whole clan renewing itself,” Sam Rainsy, Cambodia’s longtime opposition leader, told Radio Free Asia this month. “The regime has become a hereditary dictatorship.”

Young reformist

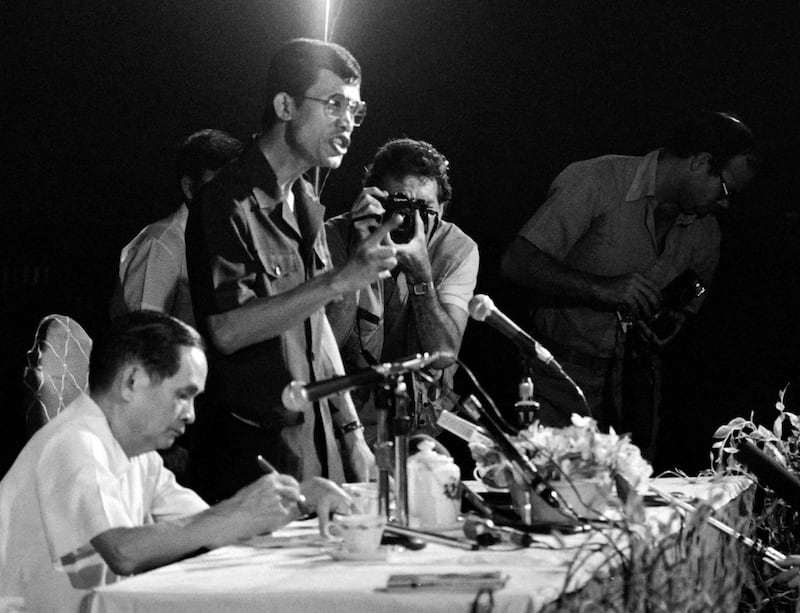

A low-level Khmer Rouge military commander who turned on Pol Pot’s regime two years before its 1979 fall, Hun Sen rapidly rose to power in Cambodia’s Hanoi-backed revolutionary regime.

In 1985, at the age of 33, he became the world’s youngest head of government and set about negotiating an end to the civil war with then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the father of Cambodia’s independence.

Viewed as a reformist at the time, Hun Sen bucked the older conservative wing of the regime to reach an agreement with Sihanouk's shadow government that resulted in the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement and the U.N.-run elections.

The globally funded nation-building exercise, estimated to have cost in the end more than $20 billion, was meant to instill in Cambodia a vibrant multi-party democratic system, complete with an independent media and a professional civil service.

Instead, a series of power grabs by Hun Sen – particularly a coup d'etat in July 1997 and the crackdown that followed the rise of Cambodia's united opposition in 2013 – mean those who openly oppose his rule could at best hope for prison or exile overseas.

After the 1997 coup, U.N. investigators found evidence that at least 40 of Hun Sen’s political rivals had been executed. In ousting his co-prime minister, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, he effectively overturned the results of the 1993 U.N.-run elections that the latter had won.

It would not be until the 2013 election that a viable challenge to his rule would re-emerge, when two long-bickering opposition parties merged into the Cambodia National Rescue Party and almost came to power in an election they said they only lost due to voter fraud.

Months of demonstrations calling for a new vote followed. When the protests later dovetailed with a nationwide strike of garment workers calling for an increase in their $80 minimum monthly wage, the government responded with violence. Military police shot dead at least five of the workers, injuring and jailing dozens more.

Hun Sen was once a hope for change but has become “the one who destroyed the political system in Cambodia,” said But Buntenh, a monk who helped lead protests after the disputed 2013 election before fleeing in 2017 amid a crackdown on regime critics.

“I recognize that he contributed to the rebuilding of Cambodia after the genocide, even though that had included him as a commander of the genocide,” But Buntenh, who now lives in Massachussets, told RFA. Hun Sen also was instrumental in the development of the Paris Peace Agreement.

“That I accept and I appreciate,” he said. “But the people hate him because he took full control and ruled the country with his entire family, and takes Cambodia, as a nation, to belong to his family.”

Succession, ‘HBO-style’

Maintaining power has required more than just the violent vanquishment of foes. Hun Sen has also had to keep his own party behind him, even when not everybody has seemed on board.

In the end, Hun Sen’s own succession plan required him to cut similar handover deals with Interior Minister Sar Kheng and Defense Minister Tea Banh.

Such an across-the-board generational transfer is necessary, explained Sam Rainsy, given the “dangerous and sensitive situation” of Hun Sen standing down while two powerful ministers with large security forces behind them could still loom over his son.

“Politically speaking, and psychologically speaking, those older officials cannot work under Hun Manet, so they all have to go,” Sam Rainsy said. “And Hun Sen has to find compensation for his colleagues, so he promised they will be replaced by their sons as well.”

But it also speaks to the fragmented nature of the government Hun Manet is taking over, one in which he lacks even the power to select his own most important cabinet ministers.

“It all resembles a kind of dynastic, corporate handoff,” Sophal Ear, a Cambodia expert at Arizona State University, told RFA. “It’s ‘Succession’ HBO-style, except within a government.”

The state is me

Though he’s standing down as prime minister, Hun Sen will hold plenty of prime positions, including Senate president, a role that will make him the acting head of state when King Norodom Sihamoni is out of the country.

"I'm not going anywhere," Hun Sen noted in an Aug. 3 speech, in which he also warned he could return as prime minister if Hun Manet is endangered. "I'm just not going to be prime minister anymore – but I will still have power, as the president of the ruling party."

The role of CPP president may have newfound prominence in Cambodia.

As the government-aligned Khmer Times noted in its report on his speech, Hun Sen pledged to respect the independence of the new government but noted their decisions "must not be different from the policy of the party that has made a promise to the electorate."

In some ways, it’s a reversion to Hun Sen’s roots, as a young revolutionary trained by political minders from Vietnam, where the Communist Party secretary-general runs the show, and the prime minister, as head of government, implements party edicts.

Stability, but for how long

At the very least, Hun Sen will be able to say he left behind a system of government that has lasted, said Carl Thayer, an emeritus professor at the Australian Defense Force Academy in Canberra and an election observer during the 1993 U.N.-run elections.

“Hun Sen will bequeath to Cambodia the longest-serving and most stable regime since Cambodia attained independence in November 1953,” Thayer said, even if the outgoing premier “also will go down in history as the destroyer of multiparty democracy in Cambodia.”

Hun Manet’s government, he added, will have a chance to “overcome baggage from the past” and forge new policy paths, as it searches for legitimacy.

One of the weaknesses of a personalist authoritarian regime is its reliance, at the end of the day, on its central persona.

Rainsy, the opposition leader, said that while the passing of ministerial fiefdoms from parent to child across the regime this week was meant to shore-up Manet’s position, there are no long-term guarantees.

“As long as Hun Sen is in good health, as long as he can show authority and threaten everybody, then this can last,” he said. “But the very day Hun Sen shows a sign of weakness, the day that his health deteriorates to the point that his authority is not as it is now, Hun Manet will not be able to hold onto his position.”