U.S. President Joe Biden told world leaders Thursday that his meeting with Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping the day prior were fruitful but did not necessarily mean the relationship between the world’s two superpowers would now be “all kumbaya.”

Biden also said the countries around the Pacific Rim should shift from focusing only on increasing trade to also consider resilience from future pandemics, supply-chain shocks and climate change.

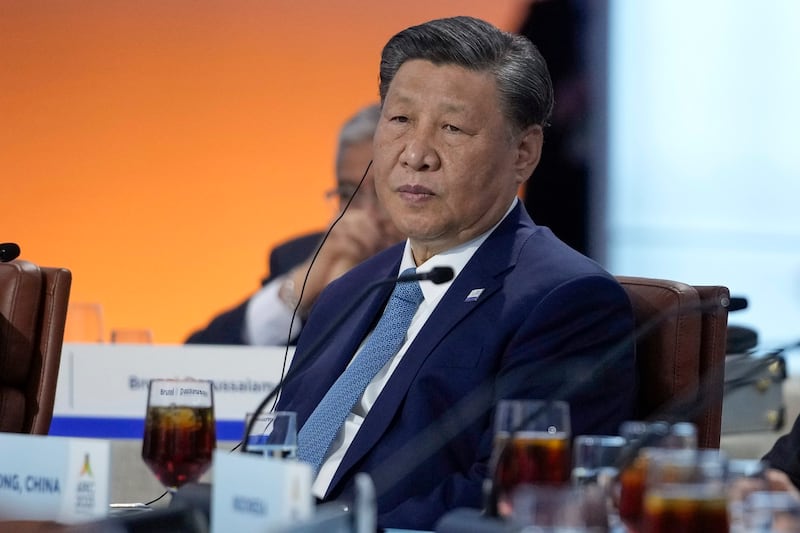

Speaking at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, or APEC, summit, Biden said he and Xi were "straightforward" with each other about their differences on Wednesday at the Filoli estate, outside San Francisco, where they met for about four hours, enjoyed a private lunch and strolled around manicured gardens.

He said the talks, which produced deals to restart military-to-military contacts, stem fentanyl exports from China and to discuss regulations on artificial intelligence, had been “candid and constructive.”

But that did not mean they were now close allies, he added.

“As my generation would say back in the day, it is not all ‘kumbaya,’ but it's straightforward. We have real differences with Beijing,” Biden said, referring to an upbeat spiritual song often cited in American politics as a metaphor for unanimity.

He said the United States would continue to take “targeted action to protect our vital national security interests” with respect to China.

“At the same time, on critical global issues such as climate, AI, counternarcotics, it makes sense to work together. We’ve committed to work together,” he said. “We're going to continue our commitment to diplomacy, to avoid surprises and prevent misunderstandings.”

“A stable relationship between the world's two largest economies is not merely good for the two economies, but for the world,” he said.

Dictator Xi?

The comments clashed with remarks made by Xi following the talks.

At a dinner with U.S. business leaders on Wednesday evening, where he made the case for continued investment across the Pacific, Xi said that Beijing was willing to go further and be “a partner and friend.”

“If one sees the other side as ‘a primary competitor,’ ‘the most consequential geopolitical challenge’ and ‘a pacing threat,’ it will only lead to misinformed policymaking, misguided actions and unwanted results,” Xi said, after pondering “Are we adversaries or partners?”

Differences between the two powers were already on display, though, before Biden’s speech to APEC leaders on Thursday morning.

Leaving a press conference following the talks on Wednesday, the U.S. president had reiterated a comment he made in June – after U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken's landmark visit to Beijing, which reopened direct talks after a year of tensions – calling Xi a "dictator."

“Well look, he is,” Biden said. “I mean, he’s a dictator in the sense that he’s the guy who runs a country that’s a communist country.”

Beijing replied that it "strongly opposed" the description. Biden, though, was not explicitly named, with Chinese state media currently in the middle of a pro-U.S. swing amid Xi's ongoing trip.

"This statement is extremely wrong and irresponsible political manipulation," foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning told reporters on Thursday, according to a report by Reuters. However, the remarks did not appear in an official transcript of the briefing posted online.

“It should be pointed out that there will always be some people with ulterior motives who attempt to incite and damage U.S.-China relations,” she was quoted as saying. “They are doomed to fail.”

More than trade

Thursday's schedule at the APEC summit is otherwise being dominated by the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, or IPEF, which the Biden administration unveiled in May 2022 and was at the time slammed by Beijing as an effort to " decouple from China."

The IPEF, which groups Australia, Brunei, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, the United States and Vietnam, is not a free-trade agreement but an economic cooperation framework seeking to establish trade rules across “four pillars” – trade resiliency, infrastructure, decarbonization and anti-corruption.

It has been described as something " nobody really understands," and the White House's plans to unveil a major IPEF trade initiative at APEC this week was rocked by opposition from Sen. Sherrod Brown, a Democrat from Ohio.

The IPEF has already stood in place of the usual efforts by U.S. presidents to promote free trade, as countries across the world continue to seek more access to U.S. markets even as such policies are perceived increasingly as kryptonite in the American electorate.

Former President Donald Trump's campaigning against the Obama administration's Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade deal, for instance, is widely viewed as contributing to his victory in the 2016 presidential election, with both U.S. parties now seemingly allergic to the deals.

Biden seemed to reference that change in the U.S. global posture over the past decade, telling leaders at the summit that “the world is fundamentally different than it was 30 years ago at the first annual APEC leaders meeting at Blake island in Washington State.”

The important thing to focus on, he said, was “not about how much we trade,” but instead “how we build resilience, lift-up working people, reduce carbon emissions, and set up our economies to succeed.”

“The idea behind this new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework,” he explained, was to tackle “urgent issues like pandemic response, vulnerable supply chains, climate change, and natural disasters, which we've learned can gravely impact our economies.”

Edited by Malcolm Foster.