A rare find in the British National Archives may provide another piece of evidence discrediting China’s claim of historic rights to the disputed Paracel archipelago in the South China Sea.

After months of scouring the archives, British journalist-turned-scholar Bill Hayton came across a semi-official document indicating that until the late Qing Dynasty, Chinese authorities still didn’t consider the Paracel Islands part of China’s territory.

Hayton, author of “The Invention of China” (2020) and “South China Sea” (2014), discovered an 1899 translation of a letter in which the Zongli Yamen -- equivalent to the foreign ministry -- of the Qing Empire informed British officials that Chinese authorities could not accept liability for the looting of a ship’s cargo in the late 1890s in the Paracels.

The letter refers to the so-called “Bellona copper case” where the German ship Bellona was wrecked in the archipelago a few years earlier and the copper cargo it was transporting was stolen by Chinese fishermen.

The Chinese government “refused compensation” for the British-insured copper because the islands were “high seas” and were not Chinese territory.

The original letter in Chinese is yet to be found, and there’s a high possibility that it has been lost or destroyed, so the translation is the first and only contemporaneous copy of the Chinese official document found to date.

Hayton said he also found the transcription of a different letter from the viceroy of the Liangguang – which comprised the regions of Guangdong and Guangxi -- to the British consul in Canton, Byron Brenan, on April 14, 1898, speaking of the same case. Viceroy Tan Zhong Lin wrote that the Chinese authorities could not possibly protect the shipwrecks as they were in “the deep blue sea,” hence they could not admit the compensation claims.

“It’s not the smoking gun, yet,” Hayton said. “But it could be helpful for Vietnam to make the case that China really didn’t care about the [Paracel] islands until later.”

The Bellona copper case was also mentioned in a 1930 letter from the French governor general of Indochina to the French minister for the colonies in which the Chinese viceroy of Canton was quoted as stating that the Paracels were “abandoned islands” and belonged “no more to China than to Vietnam,” and “no special authority was responsible for policing them.”

Such questions of historical record remain politically sensitive for claimant states in the South China Sea – not least because China justifies its sweeping maritime and territorial claims on the basis of historic rights – a position that was rejected by an international arbitral tribunal in 2016 in a case brought by the Philippines.

Nguyen Nha, a well-known Vietnamese historian, said the newly found letter could serve as another valuable piece of evidence that China did not hold ownership of the Paracels since ancient times as it always insists.

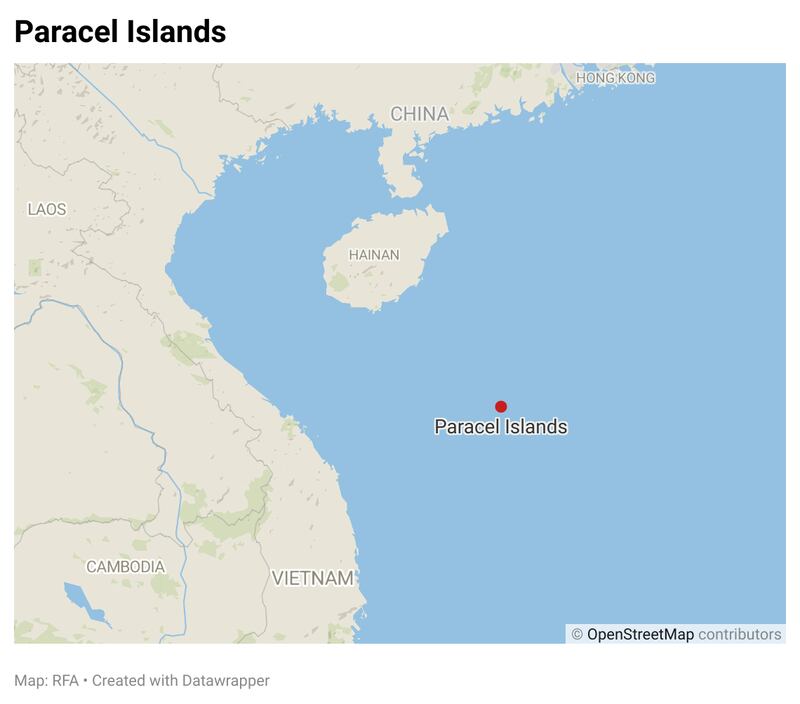

Vietnam, Taiwan and China all claim sovereignty over the Paracels which are now entirely under China’s control.

Both Hanoi and Beijing have released numerous historical documents, often replicas as original versions are almost impossible to trace, to back their claims.

Hayton’s discovery was met with interest in the South China Sea study circles.

Norwegian historian and South China Sea researcher Stein Tonnesson said the letter “may confirm other sources indicating that the Qing Empire did not at that time consider the Paracels as Chinese territory.”

“But in 1909 it did, and I’m not sure the lack of a claim in 1899 would invalidate a claim made ten years later,” he said.

Ian Storey, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, warned: “China would obfuscate the issue by calling into question the genuineness of the letter.”

Hayton’s post about the letter on social media has caused a stir, and some critics have raised questions about the accuracy of the English-language translation.

Hayton said he believes “there'll be a transcribed version of the Chinese language letter somewhere,” and he’s looking for it.

But whatever the outcome, according to Storey, “no one piece of ‘evidence’ is ever conclusive in this long-running war of documents and maps between Vietnam and China.”