A Philippine senator’s suggestion to negotiate a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea among claimant countries, and not between the whole Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China, was met with both approval and reservation from analysts.

During a hearing at the Philippine Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Imee Marcos - the committee’s chairwoman – asked if there was a possibility for “a code of conduct that includes only us claimants” in the South China Sea, parts of which are known in the Philippines as the West Philippine Sea.

"Why don't we formalize and come up with some kind of code, just between us. The first step of consensus-building is a long and torturous path," she was quoted as saying by Philippine media.

Six parties - Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam, and China - hold claims over the sea. ASEAN comprises ten member countries, among which Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand are non-claimants in the South China Sea.

ASEAN members and China signed the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) in the South China Sea twenty years ago and embarked on the negotiation on a Code of Conduct (COC) which is expected to be legally binding and playing a decisive role in diffusing regional territorial disputes.

A draft text of the COC was released in 2018 and has now entered the second reading, but the prospect of a final agreement remains dim despite China’s efforts to speed it up.

China claims “historical rights” to almost 90 percent of the South China Sea, an area roughly demarcated by the nine-dash line. Other claimants have rejected those claims and a 2016 international arbitration tribunal ruled that they had no legal basis.

‘The ship has sailed’

Some Philippine analysts were quoted in local media as saying that Imee Marcos’s idea was worth exploring.

Political analyst Anna Rosario Malindog-Uy wrote "there's no harm if the Philippines initiates a COC among the claimant-states, which include China."

“This could be faster, more efficient, effective, and less tedious,” she wrote in the Asian Century Journal.

“It will probably hasten the process, given the number of countries involved in the negotiation is fewer,” Malindog-Uy wrote.

Another analyst, Lucio Blanco Pitlo III from the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation, suggested “one of the best ways to go forward is for the four ASEAN claimants to have some consensus first.”

Pitlo was quoted in

[ BusinessWorldOpens in new window ]

as saying that if, after that, all ten members of ASEAN could reach an agreement, “they can have better leverage in negotiating with their bigger neighbor and the biggest claimant, China.”

Regional analysts however seem uncertain about the proposal.

“I think the ship on this sailed a long time ago,” said Shahriman Lockman, Director of Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies.

“To exclude the non-claimants at this stage would be a nonstarter as all ten countries have been involved for so many years,” he said.

Besides, non-claimant Indonesia has overlapping jurisdictional claims with China in the South China Sea and Singapore is a major user state given its central role in international shipping.

“Singapore also administers the flight information region (FIR) in the airspace above the South China Sea. It is not a claimant, but obviously has a huge stake in what goes on there,” Shahriman told RFA.

‘External factors’

Philippine analysts, such as Malindog-Uy, warned against what they called “external factors.”

“Countries not parties to the South China Sea dispute, like the United States, should not be involved, for it will just complicate and muddle the situation,” she wrote in her column.

Malindog-Uy’s statement resonated with those of Chinese scholars who said “some extra-regional countries with ulterior motives hope to realize their regional strategies by exaggerating the tension in the South China Sea.”

Hu Bo, Director of the Center for Maritime Strategy Studies at Peking University, wrote in an article on the South China Sea Probing Initiative website that the United States "ostensibly emphasizes maintaining a 'rules-based international order', but [is] actually trying to create a maritime order to exclude China in the South China Sea and even the Indo-Pacific region."

Hu also accused some ASEAN countries of having “some unrealistic expectations,” adding that “neither the DOC nor the COC is a platform for resolving disputes in the South China Sea.”

“Any attempt to raise a negotiating price is intended to prevent or destroy consultations,” the Chinese analyst wrote.

“Demanding too much from China is not the way to be a good neighbor and friend, nor does it serve the interests of all parties as well as the whole region,” he added.

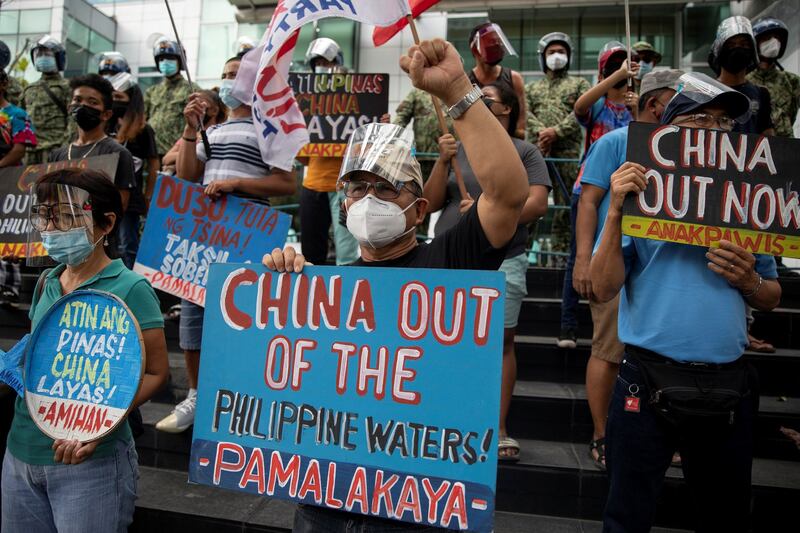

China’s behavior, on the other hand, is seen by several stakeholders in the South China Sea as aggressive and not helpful to the COC negotiating process.

Huynh Tam Sang, a lecturer at Ho Chi Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Vietnam, said a major obstacle in the negotiation is China’s maritime aggression.

“As the U.S. has been more determined to boost its engagement in the South China Sea under the motto of freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), China has at the same time stepped up its military exercises in the contested sea,” he said.

“In essence, China wants the COC to be built upon the PRC’s interests rather than those of ASEAN states,” Sang told RFA, using China’s official name - the People’s Republic of China.

Yet the analyst argued that “as the role of ASEAN has increased in the eyes of great powers like the U.S., Japan, Australia and India, the determination of middle powers like Vietnam and the Philippines will likely increase and make the conclusion of the COC within this year unlikely.”