The teaching of Mandarin Chinese is now prevalent in many government-run schools in Myanmar’s Mongla autonomous special region, local teachers say, as the remote border area in eastern Shan state that has become dependent on nearby China for business and jobs.

The Chinese have stepped in to fill a critical void in education services provided by Myanmar’s Ministry of Education in the isolated region that is geographically close to China, they say.

And Mongla leaders have welcomed the teaching of nearly all subjects in Mandarin because of the support that Chinese officials give to the region, where Burmese is usually not the first language of a diverse group of ethnic minorities.

The vast majority of Mongla residents prefer that their children receive a Mandarin-language education so they can go China for jobs, given a dearth of work opportunities in the autonomous region, educators say.

“The Chinese language is the main subject,” said Hweh Pan, a teacher at a school in the Mongla region’s Nampang district. “Mathematics is also taught in Chinese. As for the Myanmar language, it is also a subject in schools, but for the most part it is not used.”

“It’s true. Here, they don’t know Burmese,” she said. “Also, everyone around you only speaks in Chinese. From the first to the third grade, we use books from Myanmar, but for higher grades, there is interpretation. For instance, when teaching a topic, we have to tell them what it is about in Chinese.”

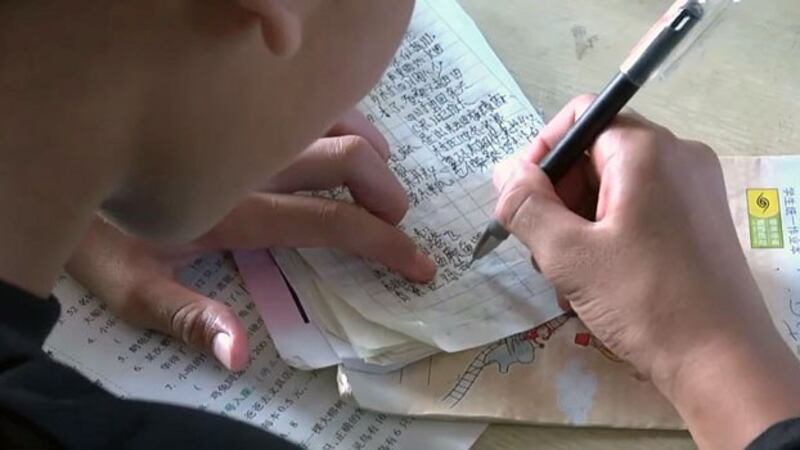

Another Chinese educator who teaches Chinese character writing to students in a Mongla region school said instruction for the facility’s more than 1,000 students is in both Burmese and Mandarin Chinese.

“[But] Chinese letters are mostly seen,” the teacher said. “I’ve also learned that the school principal is a Chinese national.”

Chinese educators go to the Mongla area, formally known as Shan State Special Region 4, to teach students in elementary through middle school, local teachers say.

Mongla authorities pay their salaries and provide teaching materials and school buildings.

Wang Jong Peng, the Chinese principal of a school in Nanpang district’s Mai Sot village, said that her school provides instruction in both Burmese and Chinese from primary school to middle school.

Besides Burmese, 13 other languages are spoken by ethnic minority groups living in the Mongla region, including Shan, Akha, Lahu, and Lweh.

Children, however, mainly speak Chinese, now the lingua franca of the region, rather than their native tongues because it will help them get jobs, educators say.

After middle school, some students stay in the area to attend high school, while others from well-off families are sent to school in China, where they will have better educational and economic opportunities and health care, they say.

Demise of Burmese language

Over the last three decades, 52 basic Burmese-language elementary and high schools have opened in the Mongla region under the auspices of the Myanmar government’s Area Ethnic People Development Project, colloquially known as Na Ta La, without the consent of locals, region officials say.

A former military regime that ruled the country initiated the original government-funded Na Ta La project to rebalance the population in ethnic minority regions with Buddhist ethnic Burmans under the supervision of the Ministry for Progress of Border Affairs and National Races Department, now called the Ministry of Border Affairs.

Members of the dominant Burman ethnic group moved to remote ethnic minority regions in Shan, Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Chin, and northern Rakhine states in the 1990s.

But Mongla authorities shut down some of the elementary schools in 2012 when tensions arose between ethnic Wa soldiers and the Myanmar military, and troops from both sides approached the Mongla region, local officials say. The schools never reopened.

The United Wa State Army arrested some Mongla troops on suspicion that they supported Myanmar forces, while government soldiers closed several bridges that linked the region to military-controlled areas in Shan state.

A few years later, other schools in Mongla region partially reopened, but they now face a shortage of educators to teach Burmese-language curriculums.

In response, regional officials have invited Chinese teachers in to fill the void so that students in all primary and middle schools jointly operated by Mongla and Chinese authorities are now taught a Chinese-language curriculum.

Today there is only one Burmese-language high school in Mongla town that serves students in all three of the special region’s districts, and two middle schools in other areas that offer students a Burmese-language education.

To make matters worse, these schools suffer from a lack of local teachers.

“We have insufficient numbers of teachers for the classes,” said middle-school educator Nu Nu Lwin. “Officially, there are only three teachers for elementary classes in a school, so one teacher is responsible for more than 60 students.”

Teachers also said the pupils have difficulty learning Burmese because of the prevalence of Mandarin in the region.

“We are always in touch with and having relationships with Chinese people, and the children are not acquiring much of the Burmese language,” said Thet Soe Oo, a Myanmar teacher in Nampang.

“It is difficult because of what they encounter on a daily basis,” he said. “They leave here and throw down their shoulder bags at home. The movies that come out are in Chinese, and so, sometimes there is no way for them to acquire Burmese. If we teach them something in [Burmese] today, they will forget it tomorrow.”

Because those who live along the Mongla region’s strip of land bordering southwestern China's Yunnan province are largely cut off from greater Myanmar, they also have come to rely on Chinese-language news for information, sources in the region say.

‘Vision for the future’

Some see the predominance of Chinese-language education as a way for China to continue solidifying its foothold in the Mongla region.

Chinese nationals have established restaurants and other businesses there as part of the country’s efforts to expand its interests and influence in Myanmar through decades of engagement with both state and non-state actors.

But the economic success of the Mongla region is largely due to Chinese involvement in casinos, the illegal wildlife trade, gambling, and prostitution.

"In many ways, Mongla represents a 'successful' outcome of decades of Chinese engagement with Myanmar's border regions: Chinese-style development based on infrastructure construction, resource exploitation, and close ties with the People's Republic," wrote scholars Alessandro Rippa and Martin Saxer in an essay on the region in the June 2016 issue of Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review.

“In this sense, Mongla can even be seen as an example of China’s vision for the future of Myanmar’s border regions,” they wrote.

Reported by Aung Theinkha for RFA’s Myanmar Service. Translated by RFA’s Myanmar Service. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.