Can manga spread awareness of the plight of Uyghurs in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) to audiences beyond the reach of traditional activism and reporting?

Japanese writer and cartoonist Tomomi Shimizu believes so—enough to have published six manga books detailing the persecution Uyghurs face in the XUAR, from everyday repression to confinement in the region’s internment camps.

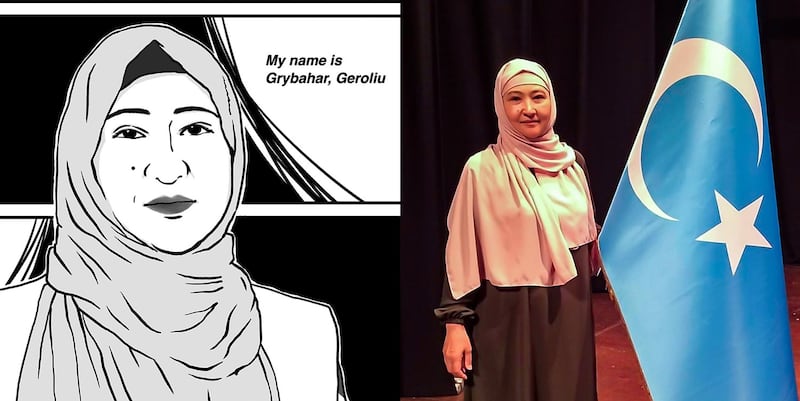

And Uyghur businesswoman Gulbahar Jelilova, whose detention for 17 months was the subject of Shimizu’s second book, says the manga treatment of her internment camp experience has drawn young people to join protests in support of Uyghurs.

Shimizu has used her writing format with particular effect to highlight the testimonies of former detainees in the XUAR’s vast network of internment camps, where authorities are believed to have held up to 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities since April 2017.

The 50-year-old mangaka’s second illustrated book on the Uyghur crisis, entitled “What Happened to Me: One Uyghur Woman’s Testimony,” attempts to describe what women experience in the camps through the testimony of Gulbahar Jelilova, a Uyghur businesswoman from Kazakhstan who was detained in the XUAR capital Urumqi for 15 months beginning in 2017.

The book, which was originally written in Japanese and translated into English, was released in Turkish on Aug. 30. It drew praise from the media in Turkey, where Jelilova now lives, part of a Uyghur exile community estimated to be 50,000 strong.

Through her artwork in the book, Shimizu pays careful attention to small details, from the expressions on the faces of Jelilova and the camp guards to closed circuit cameras mounted on cell walls. Shimizu also uses dialogue and narration to describe specific experiences of detainees, down to the tiny amount of toilet paper they were provided each day and how Jelilova—who was educated in Russian in Kazakhstan—was forced to memorize Chinese-language political songs and recite them under close scrutiny by camp security and officials. She includes a list of some 200 women who were held alongside Jelilova in various cells, based on the former detainee’s accounts.

The book also highlights the way that writers, lawyers, professors, and artists were all locked up together, despite claims by Beijing that the camps are voluntary “vocational training centers,” and includes one particularly moving story of a woman who was brought into Jelilova’s camp shortly after giving birth in a hospital, her breastmilk leaking through the clothes she was made to wear in detention.

Shimizu, who makes no profit from the books she writes about the Uyghurs, recently told RFA’s Uyghur Service through Japan-based Uyghur intellectual Gulistan, that she is pleased to know the situation in the XUAR is receiving more attention because of her manga.

“In autumn 2019, I was shocked after watching a video of Gulbahar Jelilova, who was in Turkey [at the time], speaking about [having had her hair shaved off in the camp],” she said, discussing what had drawn her to Jelilova’s story.

“I understood that not many people can get out [of the camps], that not many people can testify about them, and so I decided to use my drawings to raise international awareness about her story.”

Shimizu noted that China has been pushing the narrative that Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities are “living happy lives” in the XUAR.

“But by drawing what’s really happening, I am giving readers the chance to make their own judgment, to see that China is lying,” she said. “That’s why I drew this.”

Shimizu has another manga about the experiences of Uyghur former camp detainees slated for publication in Japan in late October and said she plans to continue working on books about the situation in the XUAR.

She said that the issue is not one for Uyghurs to address alone and expressed gratitude to the many people around the world who have volunteered their time to translate her work into languages that include English, Uyghur, Turkish, French, and Italian in recent years.

‘Important role’

RFA also spoke with Gulistan about the process Shimizu used to create her manga, which she said was a deliberate choice because of its familiarity to the Japanese audience.

“She first sketched everything out on the information she was able to gather, on what she knew about the situation, and then she showed her first sketches to camp survivor Gulbahar Jelilova and asked for feedback—whether there were things that were missing or things that Gulbahar wanted to add,” Gulistan said.

“As I see it, she’s playing an important role in introducing the Uyghur issue to readers who like the Japanese manga form, and especially in getting the attention of young readers … A lot of people are showing up at demonstrations saying they came after reading one of her works, so I think that her publicity has been very good.”

Gulistan said Shimizu’s work had received praise because she used a form that can “directly convey and describe the situation” to her readers.

“Her dream is to draw and publish works that are helpful in protecting human rights, in exposing the hidden, secretive things that are happening [to Uyghurs], things that are being misunderstood [thanks to disinformation], to wide audiences so that people will know and understand the situation,” she said.

Expressing gratitude

Jelilova told RFA that while it was difficult for her to recount what happened to her, she was very moved by Shimizu’s dedication to the project and was glad to have worked with the author.

“Tomomi, I want to express many thanks to you,” she said, adding that the manga did an excellent job of capturing her experiences in the camp.

She expressed hope for more publications and projects such as Shimizu’s manga to help draw attention to rights abuses in the XUAR.

“I’ve been testifying for two years, but I don’t even know whether [my cellmates are] alive, or whether the Chinese authorities have killed them,” she said.

“For two years I have been speaking nonstop about these girls.”

Reported by Gulchehra Hoja for RFA’s Uyghur Service. Translated by Elise Anderson. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.