Information about the novel coronavirus (nCoV) and how it has spread in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) is a “state secret” and cannot be shared with the public, according to a government employee in the region’s capital Urumqi.

On Jan. 23, Chinese state media cited local health authorities in the XUAR as saying that a 47-year-old man identified by the surname Li and a 52-year-old man identified as Gu had been confirmed infected by nCoV. Both had been to Hubei’s capital Wuhan, where the virus is believed to have been first transmitted to humans.

As of Sunday, at least 24 people had been confirmed infected in the XUAR while 1,254 had been placed under medical observation, with six in serious condition and two in critical condition, according to state media.

A report by the official Tianshan.net website said that China Southern Airlines had sent 400,000 masks and 40,000 gloves to Urumqi and the prefectural-level city of Karamay (in Chinese, Kelemayi), while authorities sent some 1,000 coronavirus test kits to the XUAR, reflecting the potential severity of the outbreak in the region.

Local officials have remained tight-lipped about how nCoV has spread in the region, where authorities have detained as many as 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities accused of harboring “strong religious views” and “politically incorrect” ideas in a vast network of internment camps since April 2017.

Reporting by RFA’s Uyghur Service and other media outlets indicate that those in the camps are detained against their will and subjected to political indoctrination, routinely face rough treatment at the hands of their overseers, and endure poor diets and unhygienic conditions in the often overcrowded facilities that experts warned recently could lead to an epidemic.

RFA recently spoke with employees of numerous health bureaus and other related offices in the XUAR to learn more about how the virus has spread, but all refused to comment, with one official saying that doing so could violate Chinese laws on divulging matters of national security.

When asked how many people had been infected, an employee at a 120 emergency call center in the seat of Kashgar (Kashi) prefecture said they did not know and referred questions to the municipal health bureau, while an emergency services staffer in the Changji Hui (Changji Huizu) Autonomous prefecture’s Sanji (Changji) city said “I cannot answer that … [because] I don’t know who you are.”

A government employee in Urumqi, when asked about the number of infected, told RFA that “I can’t talk with you on the phone about state secrets like this.”

A health bureau employee in Akto (Aketao) county, in Kizilsu Kirghiz (Kezileisu Keerkezi) Autonomous Prefecture, did not provide numbers of cases, but said that staff members had been divided into seven groups to carry out work related to public safety.

“We’re working with the Public Security Bureau (PSB) to quarantine and disinfect people coming into the county,” the employee said.

“Everyday we’re also disinfecting in neighborhoods. We’re doing this in any place where a lot of people go.”

Informing the public

Memet Imin, a U.S.-based Uyghur medical researcher, told RFA that the lack of information about nCoV in the XUAR reflects a culture in which local officials are too frightened to speak out about sensitive issues that could result in their being targeted by China’s central government.

“Under normal circumstances, for the purposes of protecting privacy, it’s prohibited to reveal private information connected to an illness, but informing the public about things like how many people have contracted a particular illness and what the symptoms of that illness are—especially in attempting to control such a serious situation as this—is really important,” Imin said.

“The more the [government] control escalates, the slower information is to spread, and the slower the information comes out, the more people end up searching for news from other sources,” he added.

“As for this virus that spread from Wuhan, what’s making people in and outside of China the most angry about it is that they didn’t hear about it [from the government] in time and that [the govnerment] didn’t allow doctors and medical personnel to actually do their work, but instead let bureaucracts and political people get involved in controlling information—people outside this field of specialization.”

Imin said that such an approach had allowed the virus to gain a solid foothold in Wuhan, leading authorities to shut down all transportation in and out of the city of 11 million people last month.

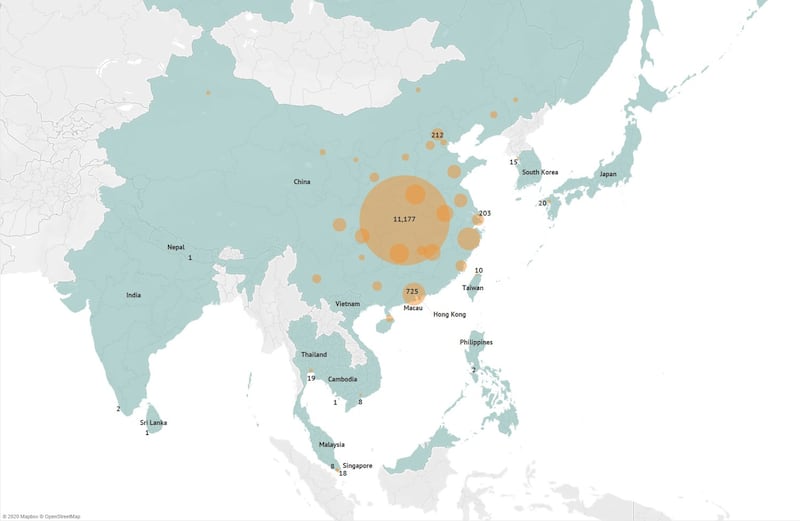

Despite the clampdown, China has seen the number of confirmed cases nationwide balloon to 17,308 as of Monday, with 362 deaths and 188 cases worldwide, including the first death outside of China, which occurred in the Philippines.

“In China, [the government] considers many matters to concern ‘state secrets,’” Imin said.

“As a result, there’s a very serious problem in the realm of information sharing. In the event of something like this illness spreading throughout the entire country, if Xi Jinping doesn’t give the go-ahead, then this kind of situation appears where people won’t talk about things to the foreign press.”

Imin said that local officials are terrified of being singled out for problems affecting the XUAR, which is a particularly sensitive region for the central government.

“If they make even the smallest mistake, they might lose all their power, and they could end up in jail,” he said.

“So, because of this, because people don’t want to make mistakes, an environment of non-work is taking shape.”

Imin pointed to reports, including by RFA, that in addition to the factor of poor hygenic conditions at the camps, an nCoV spread in the facilities is likely because the immune systems of detainees are often weakened from bad diets and even torture.

“Certainly [the Chinese government] knows about this, so perhaps as a way of trying to avoid this issue making waves internationally, it was inevitable that they would try so hard to control information about the spread of the disease in our region,” he said.

“They don’t want yet another reason for [the Xinjiang and Uyghur issue] to become a big topic of discussion.”

Detainees at risk

Sophie Richardson, New York-based Human Rights Watch’s China director, told RFA that while China’s government has done a better job in recent weeks of getting out information that people need about the epidemic and how to look after themselves, “at the same time they're also taking down information that's useful to people because it's critical of the government.”

“We're particularly concerned about people being detained or harassed for doing what the authorities refer to as ‘spreading rumors,’” she said.

“There are a lot of questions about what's happening with respect to the coronavirus and people who are in detention or whose movement is otherwise limited, and so those conditions certainly apply to Uyghurs,” Richardson added.

U.S. author and commentator Gordon G. Chang told RFA that the response by the Chinese government to the coronavirus outbreak hasn’t changed much from how it acted during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which originated in southern China in 2002 and went on to infect more than 8,000 people and leave nearly 800 dead in 17 countries.

“If there's any difference, it's only because social media plays a far more important role in shaping Chinese national conversations,” he said.

“But if it weren't for social media, Beijing's response would have been exactly the same—secrecy until they can no longer cover it up.”

Chang noted that Beijing recently touted that local authorities had constructed a brand new hospital in Wuhan to assist with containing the virus within 10 days, but said “there was no need to build a hospital in the first place.”

“Because of Beijing's hierarchical policies, hierarchical structure, and its absolute demand to control the narrative—its suppression of news—this is what caused this outbreak to become a crisis,” he said.

Reported by Shohret Hoshur and Mamatjan Juma for RFA's Uyghur Service. Translated by Elise Anderson and Alim Seytoff. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.