To the North Vietnamese communists, super-spy Pham Xuan An was a patriot and a hero. To many South Vietnamese, he was a traitor.

Following a long battle with emphysema, An died on Sept. 18 at the age of 79 in a military hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon.

An was given full honors at a funeral on Sept. 23. He had been granted the title of Hero of the People’s Armed Forces and retired with the rank of major general.

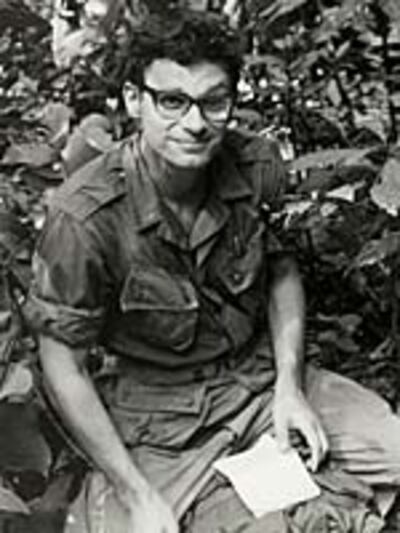

The death of Pham Xuan An, a Viet Cong spy who worked for Time magazine and other U.S. news organizations during the Vietnam War, will surely stir new debate over the role of the media in that conflict.

Some contend that An was an agent of influence, using his wide contacts with the Western media to sow disinformation and doubt about the value of supporting a “corrupt” South Vietnamese regime. An himself said his role consisted only of gathering strategic intelligence and assessing the relative strengths and weaknesses of the combatants. He often said that peddling false information to the Western press would have exposed him.

Bruce Palling, writing for The Independent of London, says An should rightly be viewed as one of the greatest spies of the 20th century.

Nearly everyone agrees that An was well connected with both U.S. and South Vietnamese officials, military officers, and intelligence agents. He had a dry, caustic sense of humor and a seemingly laid-back, unhurried style that he could use to draw all sorts of people into lengthy conversation.

An’s name means “hidden” in Vietnamese.

©;

Learned from Americans

Larry Berman, a professor of political science at the University of California in Davis, is close to completing a book about An based on more than 100 interviews with An in Ho Chi Minh City. He says An picked up many of his skills while studying at Orange Coast College (OCC) in Costa Mesta, California.

“He learned from the Americans how to be a schmoozer,” says Berman. “He had great wit. He was always joking around…. But he also had a photographic mind.”

An was in many ways the perfect spy. He led a modest but bourgeois lifestyle. He enjoyed songbirds and gambled on fighting cocks. He loved dogs, especially the big German shepherd that kept him company at the time.

He would sit for hours chain-smoking American cigarettes and trading stories with other South Vietnamese journalists at Givral’s coffee shop in the center of Saigon.

He adopted several humorous titles for himself, such as “General Givral.”

But we now know that he turned to deadly serious work at night, photocopying documents, typing up reports, and hiding film inside grilled pork wrapped in rice paper.

Disillusioned after Communist takeover

An quickly became disillusioned with the Vietnamese communists once they took power. In answer to a question last year from three journalists, including an editor from RFA, he said that the communists had become “much more corrupt” than the leaders of the old South Vietnamese regime.

In the end, the new regime distrusted An. In 1979, they sent him to Hanoi for a year of “reeducation.” Then they kept him under virtual house arrest for several years. They barred him from traveling abroad, refusing to give him a exit visa for a conference on Vietnam in New York.

The regime appears to have regarded An with suspicion because he was close to many Americans and because he helped a number of South Vietnamese former officials and others escape from Saigon just before the city fell in 1975.

Most prominent among those rescued by An was Dr. Tran Kim Tuyen, former head of an intelligence network in the early 1960s under then South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. An managed to get Tuyen on one of the last U.S. helicopters leaving Saigon before North Vietnamese tanks crashed into the city.

An owed a great deal to the diminutive Tuyen, whom some Americans called “the little doctor.” When An returned to Saigon in 1959 after studying in the United States, the Diem regime was on the offensive against communist agents. Many had been killed.

An used his family connections to secure a job under Tuyen in Diem’s presidential palace. This gave An excellent cover. When Tuyen was ousted for plotting against the Diem regime, An moved on to a job at the Reuters news agency. After Diem was overthrown, Tuyen became a major source of information for An.

Assessing the damage

Bruce Palling, a former Vietnam War correspondent, writes that An deserves high ranking as a spy because he played a crucial role in two turning points in the war – the battle at Ap Bac in the Mekong Delta in 1963 and the 1968 Tet offensive.

An’s analysis of U.S. counter-insurgency strategy and tactics was apparently perceptive enough to help give the Viet Cong confidence that they could take on major South Vietnamese army units for the first time in the early 1960s.

They did just that in January 1963, outside the Mekong Delta hamlet of Ap Bac, 40 miles southwest of Saigon. Three well-prepared Viet Cong companies battered an entire South Vietnamese army division that was supported by artillery and U.S. advisers and helicopters.

In advance of the Tet offensive, An helped to select targets in Saigon for the Viet Cong, driving agents around Saigon in his old Renault car. The car can now be seen at a military museum in Hanoi.

The Tet offensive was a military disaster for the Viet Cong but turned into a psychological victory because of its impact on the United States.

But many questions remain.

Was An really one of the greatest spies in world history, as Bruce Palling suggests? Palling qualifies this by acknowledging that it’s “tricky … to attempt to quantify the impact of secret intelligence on the outcome of a prolonged war.”

How much damage did An do? No one really knew or knows for sure, except perhaps An himself, a few key agents in the South and An's masters in Hanoi.

And as Larry Berman puts it, even after numerous lengthy conversations with An, An “told me what he wanted to tell me.”

Dan Southerland is Executive Editor at Radio Free Asia. In the 1960s and 1970s he covered the Vietnam War for United Press International and The Christian Science Monitor.

For a more personal view, read Vietnam Diary 5: 'The Perfect Spy'.