A Hong Kong court on Thursday found two editors of the Stand News guilty of conspiring to publish seditious material, the latest casualties of draconian national security laws imposed on the once freewheeling international financial hub by Chinese and local authorities since 2020.

In the first sedition conviction against any journalist since Hong Kong's handover from Britain to China in 1997, the now-defunct publication's former editor-in-chief, Chung Pui-kuen, and former acting editor-in-chief, Patrick Lam, could face a maximum prison term of two years.

The journalists for Stand News were charged with conspiracy to publish seditious material under a British colonial law that had not been used until 2020, when China imposed new national security laws in response to mass pro-democracy protests in the city in 2019.

Is the punishment of the Stand News journalists an isolated case?

Several independent news outlets in Hong Kong have been shuttered and had staff arrested and prosecuted after the National Security Law in Hong Kong was imposed by China on June 30, 2020, and the Hong Kong government passed Article 23 Safeguarding National Security Law in March.

Stand News was forced to cease its operations after police raided its office on Dec. 29, 2021, arresting senior staff and freezing its assets. Days later, another news outlet, the Citizen News, announced it would cease operations, citing the deteriorating media environment and risks to its staff.

By far the most influential outlet of the more than seven independent media outlets to be silenced was the pro-democracy Apple Daily newspaper, which was forced to close in June 2021 following police raids on its newsroom and the freezing of its assets.

Apple Daily's founder, Next Digital media mogul Jimmy Lai, a vocal critic of China for decades, is currently standing trial for "conspiracy to collude with foreign forces" and "collusion with foreign forces" under the 2020 National Security Law.

In May 2023, Hong Kong's Chinese-language newspaper of record, the Ming Pao, last week canceled a regular comic strip by Wong Kei-kwan, better known as Zunzi, following an onslaught of public criticism from government officials over his satirical cartoons on local politics.

In May of this year, Ronson Chan, a former deputy assignment editor at Stand News and outspoken critic of diminishing press freedom in the city, announced he would not seek re-election as chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists' Association, saying he had been told that the organization would continue to be targeted by the authorities if he didn't step down.

What do media freedom and human rights watchdog groups say about Hong Kong’s situation?

In the global press freedom ranking issued annually by Reporters Without Borders, or RSF, Hong Kong stood at 18th out of 180 countries and territories in 2002, but fell to 148th in 2022. The city's ranking now stands at 135, between the Philippines and South Sudan.

Freedom House, in a broader survey of global civic freedoms that ranked Hong Kong "partly free," gave the territory a low score of 1 out of 4 when it comes to having "free and Independent media."

The Washington-based group noted the June 2023 closure of Citizens’ Radio, after the government blocked its access to donations, citing the National Security Law. And public broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong "had a reputation for independence before the government effectively took control of its output in 2021," it said.

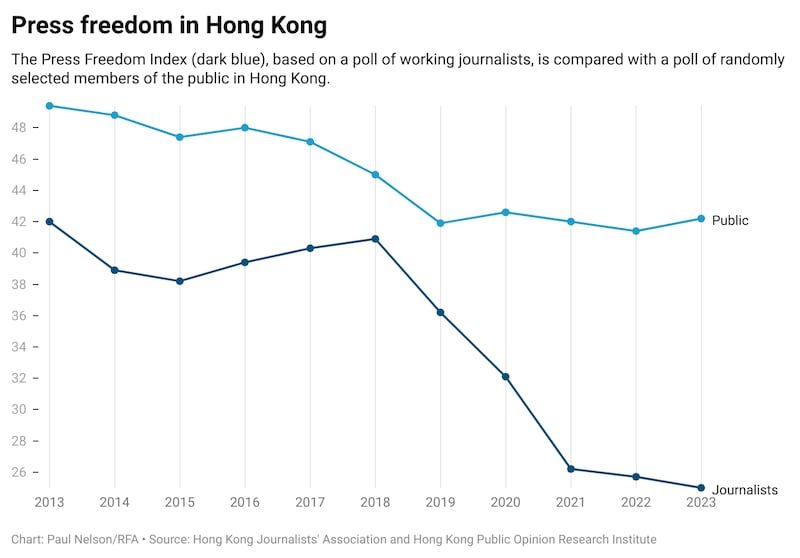

The Hong Kong Journalists' Association, in a Press Freedom Index published just a week before Thursday's Stand News verdict, found that respondents said press freedom in the city had fallen to its lowest point since the annual survey of working journalists began 11 years ago.

More than half of the 251 journalists who responded to the survey said press freedom had declined over the past year, and more than 90% of respondents said conditions had declined overall for the fifth year in a row.

RSF reckons that at least 28 journalists have been prosecuted under the 2020 National Security Law.

How have media outlets and journalists responded to the repressive atmosphere?

While officials in China and Hong Kong repeatedly say that journalists are safe to carry out "legitimate" reporting activities under both the 2020 National Security Law and Article 23, reporters told RFA Cantonese in May that they face too many serious risks.

RSF noted in its annual survey that in the wake of the 2020 security law, “a handful of new, small-scale news outlets have been founded by some of the journalists who lost their jobs, and diaspora media outlets are establishing themselves around the world.”

Foreign media were also affected by the draconian laws, with The New York Times relocating its digital news operations to Seoul and other outlets moving their staff to the vibrant democracy of Taiwan. The island ranks 27th on the RSF index.

Taiwan's Foreign Ministry said in 2022 it had gained 63 foreign correspondents and 29 news organizations since 2020, as media companies relocated staff from Hong Kong and China, whose already poor media climate deteriorated further amid U.S.-China tensions and the COVID pandemic.

In late March, Radio Free Asia, an independent media outlet funded by the U.S. Congress, announced the closure of its 28-year-old Hong Kong bureau, saying that Article 23 had raised safety concerns for its reporters and staff members.