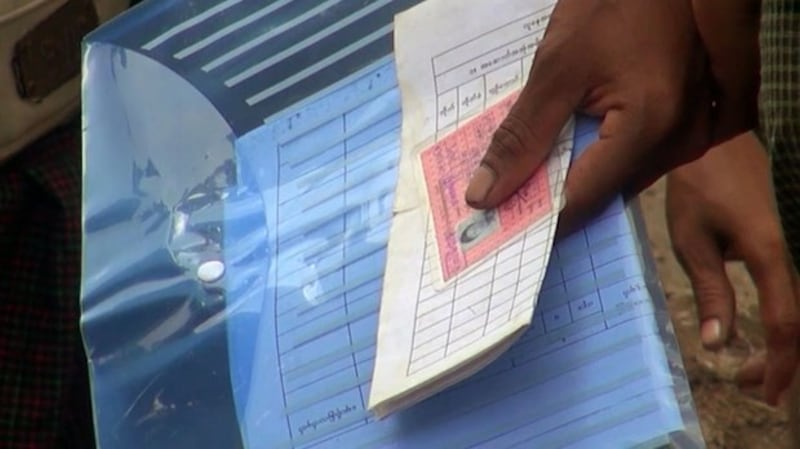

For the Burman majority in Myanmar, obtaining a national identification card – usually needed for accessing medical services and public schools, opening a bank account or getting a passport – is a relatively easy process.

But for the country’s Karen, Chin, Shan and other ethnic minorities – about a third of the population – obtaining an ID card is a complicated ordeal, and having one can often do more harm than help.

Identification cards reveal the holder’s ethnicity and the geographic area he or she is from, so that information could link them to resistance groups like the People’s Defense Force that are fighting the military after the 2021 coup, thereby putting a target on their backs.

“There's no real use (for ID cards), except for the fact that you're exposing yourself to more scrutiny by going through that kind of complicated official process,” said Za Uk Ling, the deputy director of the Chin Human Rights Organization. “These days, people try to stay as low profile as they can, avoiding any contact with local officials.

There are other complicating factors, too. Some minorities don’t want to apply for ID cards under the junta, and thereby recognize its legitimacy.

And some administrative offices that issue ID cards have been destroyed or shut down due to the fighting.

Many simply don’t have any form of identification, and so are officially stateless.

‘Lost our chance’

But that can cut them off from opportunities and basic services.

For example, five students at Laung Lin’s school in Mawlamyine, in southern Myanmar, were thrilled to gain acceptance into Thai universities. But they were unable to obtain an ID card needed to get a passport required to travel because the local junta-run office has been closed amid turmoil in the country.

“I feel like we lost our right, our chance. We should be able to accept these opportunities – but we can’t,” Laung Lin said, asking to go by a nickname. “What if that village is not safe? If there’s war, you cannot do it at all. That’s been difficult for us.”

Ying Kawn Tai, a teacher who works for Shan education accessibility in Thailand, says that access to national identification has always been a struggle in Shan State, in eastern Myanmar, but has become almost impossible since the coup. She estimates that up to half of Shan people – roughly 2 million people – don’t have a citizen ID card.

Most government-run schools require an ID card to attend, but many Shan people who have fled to the Thai border don’t have any documentation. And there are very few Shan language schools which they can attend, she said.

Job hassles

Another problem is that traveling between states without proper identification can be risky. With high unemployment in Kayah State, those seeking work in nearby states could be arrested at checkpoints manned by junta soldiers.

Without an ID card, a whole slew of activities is difficult or impossible. “Even bank accounts, even to register mobile [phone], SIM cards – we can’t do it if we have no ID,” Zue Zue, who works on education within the Karenni State Consultative Council said.

Further south, in Kayin State, where 350,000 people displaced by fighting are mostly living in camps, the problem emerges first with birth certificates.

The health department of the Karen National Union, which has been fighting the military for greater autonomy for decades, keeps records of children born in the camps. But it doesn’t issue any sort of birth certificate to the parents because the health department doesn't have the funding, centralized office or international recognition to do that.

And without that documentation, applying for further types of identification as the child grows up becomes difficult.

"If we start issuing the birth certificates, then the identifications or the passport or the ID cards, everything will follow after that,” a Karen Department of Health and Welfare spokesperson said, asking for anonymity for security reasons.

Educational hurdles

Schools in some areas go up to grade 10, and local educators would like to offer education to grade 12. But even if they did, taking the nationwide 12th grade examination requires an ID card.

“If you do not have an ID card, you can’t do that type of examination,” said Zue Zue.

While she says they’re in the beginning stages of discussing an alternative ID system, they still face challenges in obtaining resources to complete such a task while focusing on humanitarian aid. “We have a solution, but we don’t have the support to source that solution,” she said.

Other states have begun adopting similar measures. In Kachin State, National Unity Government Deputy Education Minister Ja Htoi Pan says students can use reference letters to enroll in school, rather than identification cards.

“People use different methods to verify their ID, it depends on the situation, it depends on the school,” she said. “Some schools require their recommendation from a respectable person, a reference. Those are the temporary, interim arrangements.”

Edited by Malcolm Foster.