In the western Thai town of Mae Sot, the Yaung Chi Oo Workers Association helps migrants from neighboring Myanmar who fall victim to traffic accidents, which the group says happens every day.

Moe Kyaw, the association’s joint secretary, recalls a particularly heart-wrenching case involving a Myanmar student struck by a car while crossing the road. The student’s parents, undocumented and fearful of repercussions, were hesitant to seek justice – a common predicament for many Myanmar migrants in Thailand.

“They said, ‘just pay for the hospital expenses. Just help us treat our child’s injuries.’ They didn't want to file the case at the police station or in court,” Moe Kyaw said.

That unfortunate student is not alone in a country with one of the world’s worst traffic-safety records that has become home to two million legally registered Myanmar migrants and the estimated millions of undocumented ones.

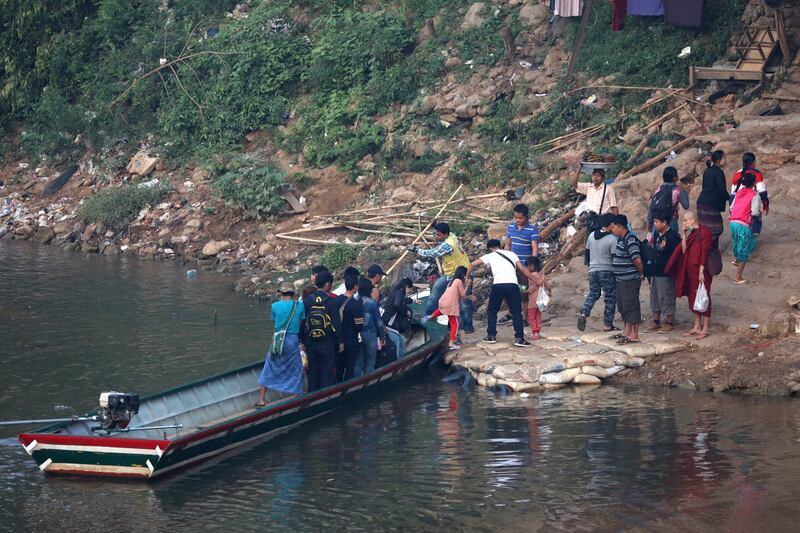

Political turmoil in Myanmar since the military ousted a civilian government in 2021 has driven hundreds of thousands of people across the border into Thailand. Reflecting that demographic shift, the number of accidents involving people from Myanmar has risen sharply.

Data for 2023 from the Road Accident Victims Protection Company shows that 380 Myanmar nationals were killed and more than 8,000 were injured in road accidents. That was a sharp increase from 2021, when there were 206 deaths and fewer than 1,400 injuries.

Statistically, Myanmar nationals are the most common victims of traffic accidents in Thailand, after Thais, dying more than five times as often as Cambodians and sustaining injuries five times more frequently than Laotians.

While the growing population of Myanmar migrants would appear to explain the figures, community workers also point to a rise in accidents related to people-smuggling, which doubled in at least one Thai border province after Myanmar's military coup.

Drivers bringing people in run into trouble on mountainous, and sometimes poorly maintained, roads as they try to avoid checkpoints or as they speed away from police patrols, welfare groups say.

Koreeyor Manuchae, project coordinator for advocacy organization Migrant Working Group, said police largely can’t, or won’t, see a connection between people-smuggling and traffic accidents and so ignore the problem meaning there’s no incentive for drivers to try to improve safety.

A senior police officer in one border area, where emergency workers say there is a shocking accident toll, waved off the issue telling RFA recently they “don’t have any trouble” with migrants.

Thailand’s Department of Land Transport did not respond to inquiries from RFA about traffic accidents linked to migration.

Struggle for compensation

For many families back in Myanmar, remittances from relatives working abroad are a lifeline. However, when an accident interrupts the funds, compensation holds out hope but the process to access it is often an insurmountable hurdle.

Under Thai law, accident victims or their families can claim up to 500,000 baht (US$15,300) in cases of permanent disability or death but Koreeyor said getting those funds is a daunting job.

Victims or their relatives have to deal with travel documents, overcome a language barrier and navigate the red tape of claims and insurance policies.

“You have to take a check to the bank, open a bank account to get the money, then you can withdraw it. The problem is, if your relative is from Myanmar, with no passport or work permit, the bank won’t allow you to open an account,” Koreeyor told Radio Free Asia.

Often exasperated and intimidated victims will just settle for whatever compensation is offered, which can be much less than what they are entitled to, she said.

RELATED STORIES

[ Thailand should end Myanmar junta’s control over migrants: NUG Opens in new window ]

[ Shuttered Thai offices leave Myanmar migrants in legal limbo Opens in new window ]

[ Myanmar’s junta halts passport conversion as Thailand mulls worker amnesty Opens in new window ]

Undocumented workers in Thailand are further deterred from pursuing compensation because they fear being deported if they present themselves to authorities in the course of filing a claim.

Myanmar’s political crisis has also complicated the situation for its citizens dealing with the aftermath of accidents in Thailand.

The Myanmar embassy in Bangkok used to be a source of help in finding the families of people killed or helping survivors with identity documents to claim compensation.

But many Myanmar citizens in Thailand now see the embassy as an outpost for the unpopular junta serving the interests of the military, in particular through various fees the junta levies on migrants through the embassy as it seeks foreign exchange.

Since Aug. 1, the junta has imposed taxes and mandatory remittances on migrant workers in Thailand, of more 6,000 baht (US$170), which must be paid through military-owned banks at an artificially low exchange rate.

Family members must now pay that fee on behalf of a deceased relative or the embassy will not help with necessary documentation, said the Foundation for Education and Development, or FED, a human rights and social welfare group working with Myanmar migrants.

“It costs more than in the past, going through these processes. It’s really challenging for migrants to get proper compensation,” said Min Oo, FED’s project coordinator.

The foundation used to depend on the embassy for help with accident victims but now it refuses to deal with it because of its association with the junta, Min Oo said.

Myanmar’s embassy in Bangkok did not respond to efforts to seek comment.

Khet Mar contributed to this report.

Edited by Taejun Kang.