Two years ago, the Myanmar junta ousted a democratically elected government in a coup, claiming election irregularities that military regime leaders have failed to prove. In the months since, the military’s efforts to consolidate power has created a calamity that has left thousands dead and forced more than 1.2 million citizens from their homes.

Conditions in the country have “gone from bad, to worse, to horrific for untold numbers of innocent Myanmar people,” Tom Andrews, the United Nations' special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, said in a recent speech urging member countries to take action to address the crisis.

“The Myanmar military is committing war crimes and crimes against humanity on a daily basis, including sexual violence, torture, the deliberate targeting of civilians, and murder.”

In September, for example, military helicopters swept over Tabayin township in Sagaing to mount a surprise attack on a local school.

Junta leaders later claimed the facility was providing shelter for resistance fighters, but villagers said that wasn’t true.

The helicopters opened fire in daylight, during school hours, killing 13 people, including seven children – leaving bodies scattered among notebooks and backpacks with images of popular cartoon figures.

Phone Tayza, a 7-year-old boy, was among those killed. His mother found him moaning in pain, suffering from severe wounds to his head, hand and thigh.

It’s a scene that has recurred with heartbreaking regularity since the coup.

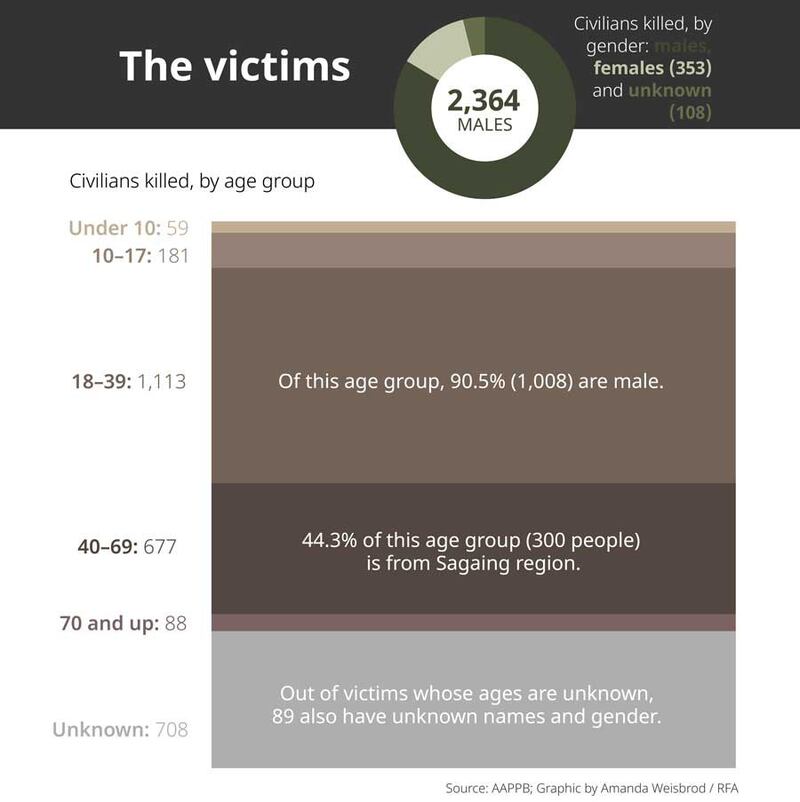

In total, military attacks have killed 265 children in Myanmar over the past two years, 59 of whom were 9 years old or younger.

In December, Khant Phyoe Thu, 9, was shot and killed by junta troops as he tried to escape his Wae Daunt village in Sagaing with his family. That day, more than 900 villagers fled when a column of 80 soldiers attacked, believing that a People’s Defense Force militia was operating there.

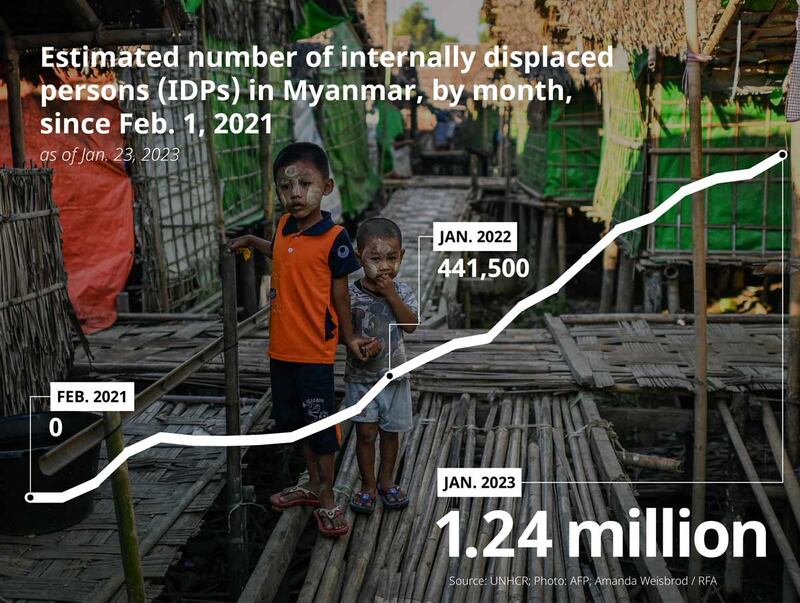

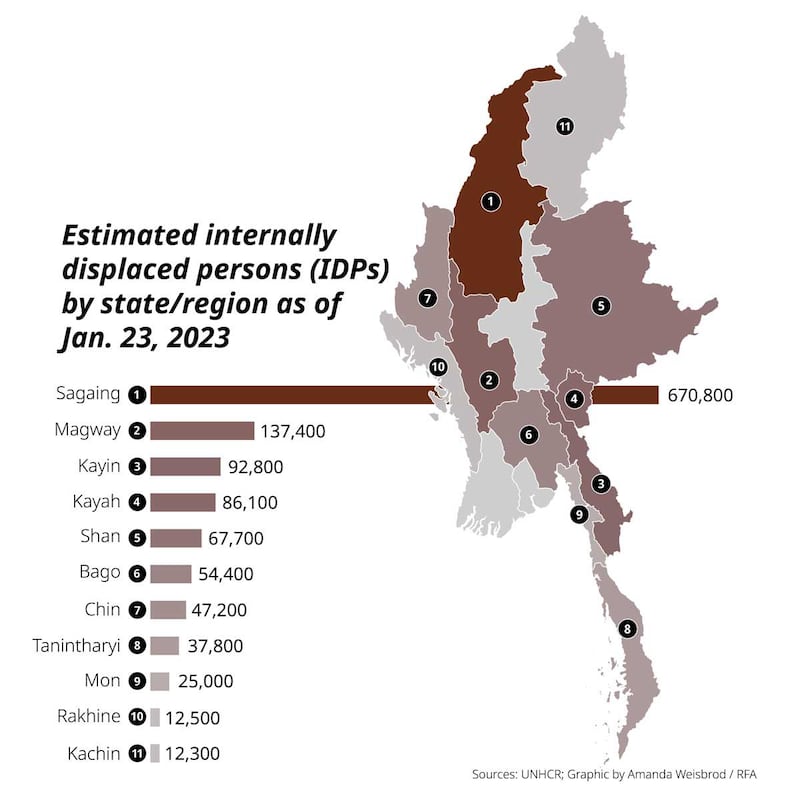

At least 1.2 million people have been forced to flee their homes due to the post-coup fighting – roughly 2% of the country’s population. A similar percentage of Americans forced to flee would equal the population of Tennessee.

Some displacements are only for a day or two. But others are on the run for weeks or longer. They often lack adequate housing, food and medical care, aid groups say. Immunizations have decreased significantly since the coup, putting children at risk of dying from otherwise preventable diseases like measles and polio.

In addition to the 1.2 million people internally displaced, the United Nations said in October that at least 70,000 Myanmar refugees had left the country entirely, where they remain vulnerable to labor exploitation and other abuses.

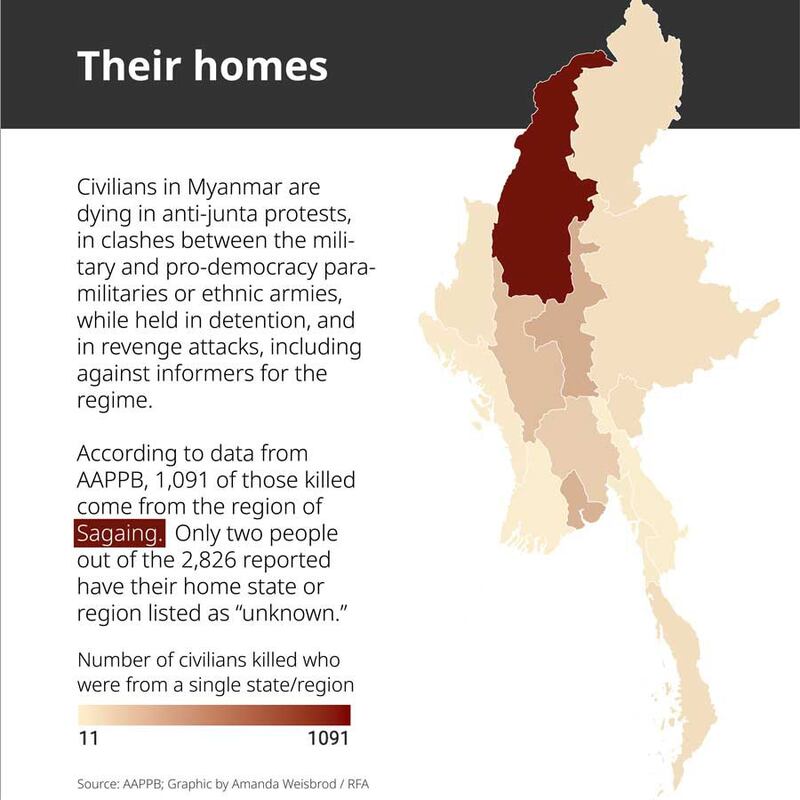

More than half of the people counted as internally displaced live in Sagaing, an agriculturally rich region in northwestern Myanmar that has become a hotbed of resistance to the regime.

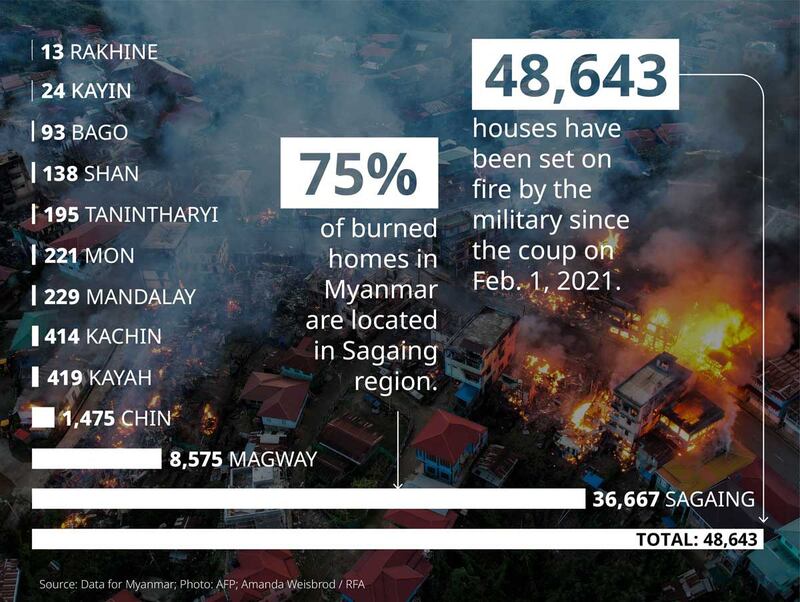

In its ruthless counterinsurgency campaign, military forces have also burned more than 48,000 homes in Sagaing, around 75% of the total number of homes set ablaze throughout Myanmar.

On two occasions, RFA Burmese Service reporters have acquired video evidence that appears to show evidence of torture committed by the hands of junta soldiers. One cell phone apparently belonging to a soldier contained a video in which soldiers boasted about killing people and included photos of them posing next to blindfolded and bound victims; another shows a brutal interrogation in Kayah state.

Deputy Information Minister Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun said the military would investigate the first incident, but no results have been announced.

Despite the brutality, the military has been unable to bring the people to heel.

“The people in this region are now fighting the regime with a persistence and courage never seen before,” Tint Swe, a former lawmaker for Sagaing’s Pale township, told RFA earlier this year.

An ethnically diverse country, Myanmar is no stranger to conflict. Ethnic armed organizations have fought the majority-Burman military for greater autonomy for decades. But the post-coup fighting might be unique in its breadth.

Myanmar’s military has clashed with Rakhine, Chin, Kachin, Shan, Karenni and Karen forces and also dozens of pro-democracy militias where the fighters are Burmans.

Thousands of junta forces have reportedly been killed, but the military’s superior arsenal of heavy artillery and attack planes and helicopters bought from Russia and China has largely kept its enemies away from the military’s power center of Naypyitaw.

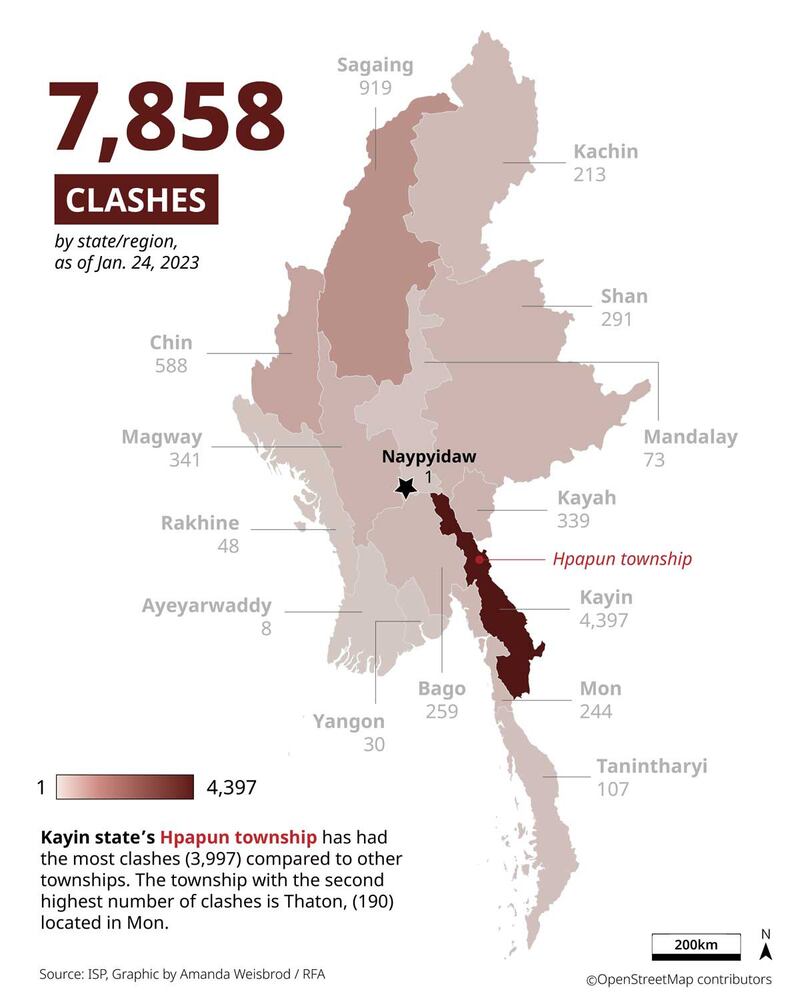

Of the 7,858 clashes between military and opposition forces, only one has taken place within the borders of the heavily guarded capital. The disparity in weaponry has led to calls for no-fly zones and the sale of surface-to-air missiles to resistance fighters, but there’s been little action on either front.

Outgunned democracy proponents have also tried to resist through mass protests and a worker’s strike known as the Civil Disobedience Movement, or CDM, drawing a predictably harsh response from junta leaders.

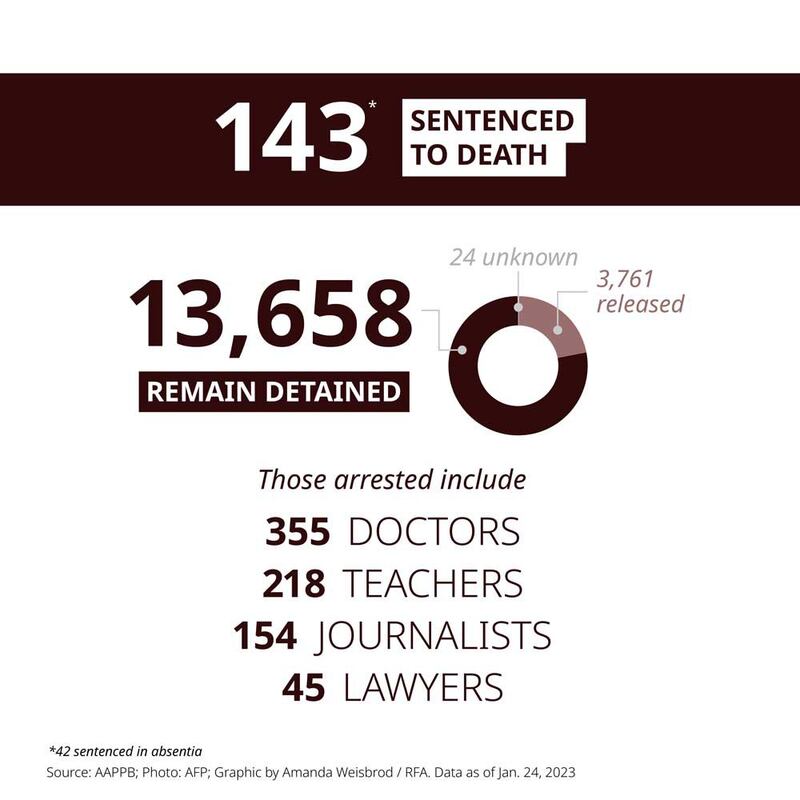

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), 17,481 political prisoners have been arrested since the coup – with 13,680 still detained. Among the prisoners are leaders of the deposed National League for Democracy, which won landslide elections in 1990, 2015 and 2020.

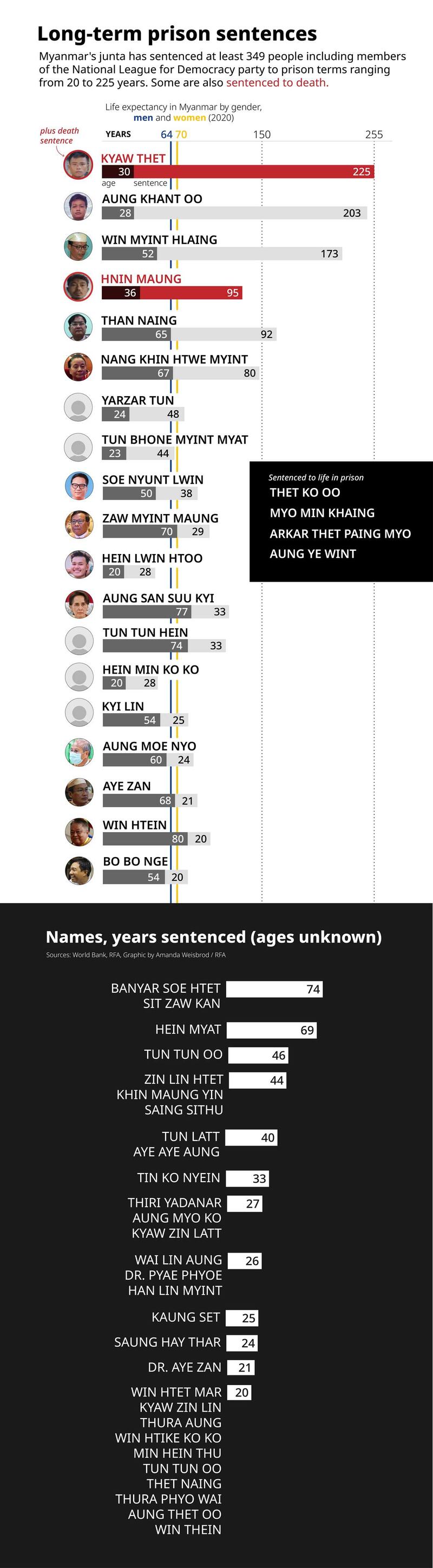

Political opponents and other democracy activists have been sentenced to absurdly long prison sentences . Kyaw Thet, 30, was given 225 years, and Hnin Maung, 36, was given 95 years. They were also sentenced to death, meaning they could face execution in coming months.

Win Myint Hlaing, a 52-year-old former NLD lawmaker, was sentenced to 148 years in prison following his conviction on eight terrorism charges. Both men were members of a militia opposing the military.

Former State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi, who is 77, is now serving a 33-year sentence that is only expected to grow as the junta stacks up the charges against her.

In June, the junta executed a former lawmaker and three other democracy rights activists, drawing international condemnation. Tom Andrews, the U.N. rapporteur, called the executions “premeditated murders committed without even the pretext of due process of law.”

Veteran activist Ko Jimmy was one of the four executed, accused of threatening “the public tranquility.” He was a celebrated author and poet who had spent 20 years in prison in Myanmar under a previous military regime for his fight for freedom.